Stablecoins

Economic, Technological and Geopolitical Superconductors

Written by Munehisa. To contact us reach out to @munehisa_asxn or @fromm_asxn on telegram.

Thanks to SS and Nathan for their thoughtful comments and feedback.

You can checkout out our stablecoin dashboard that we reference throughout the report here:

Executive Summary

Throughout history, money has consistently evolved to fulfill three core functions, as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account, while a relentless drive for faster settlement, lower costs, and borderless usability has propelled its transformation from localized barter systems to today’s global digital networks.

Since the end of World War II, the U.S. dollar has emerged as the dominant global currency, meeting the key properties of money more effectively than any other.

Stablecoins represent the next phase in the evolution of money and payments, forming the foundation of a financial system with faster settlement, lower fees, seamless cross-border functionality, native programmability and a strong auditability trail. Today’s stablecoin landscape consists of several distinct types of stablecoin, primarily differentiated by their collateral backing, degree of decentralization, and the mechanism used to maintain their peg.

Stablecoins and specifically dollar denominated stablecoins are highly demanded for a variety of use cases: store of value, remittance, payments, yield generation, crypto trading & as shadow monetary policy tools.

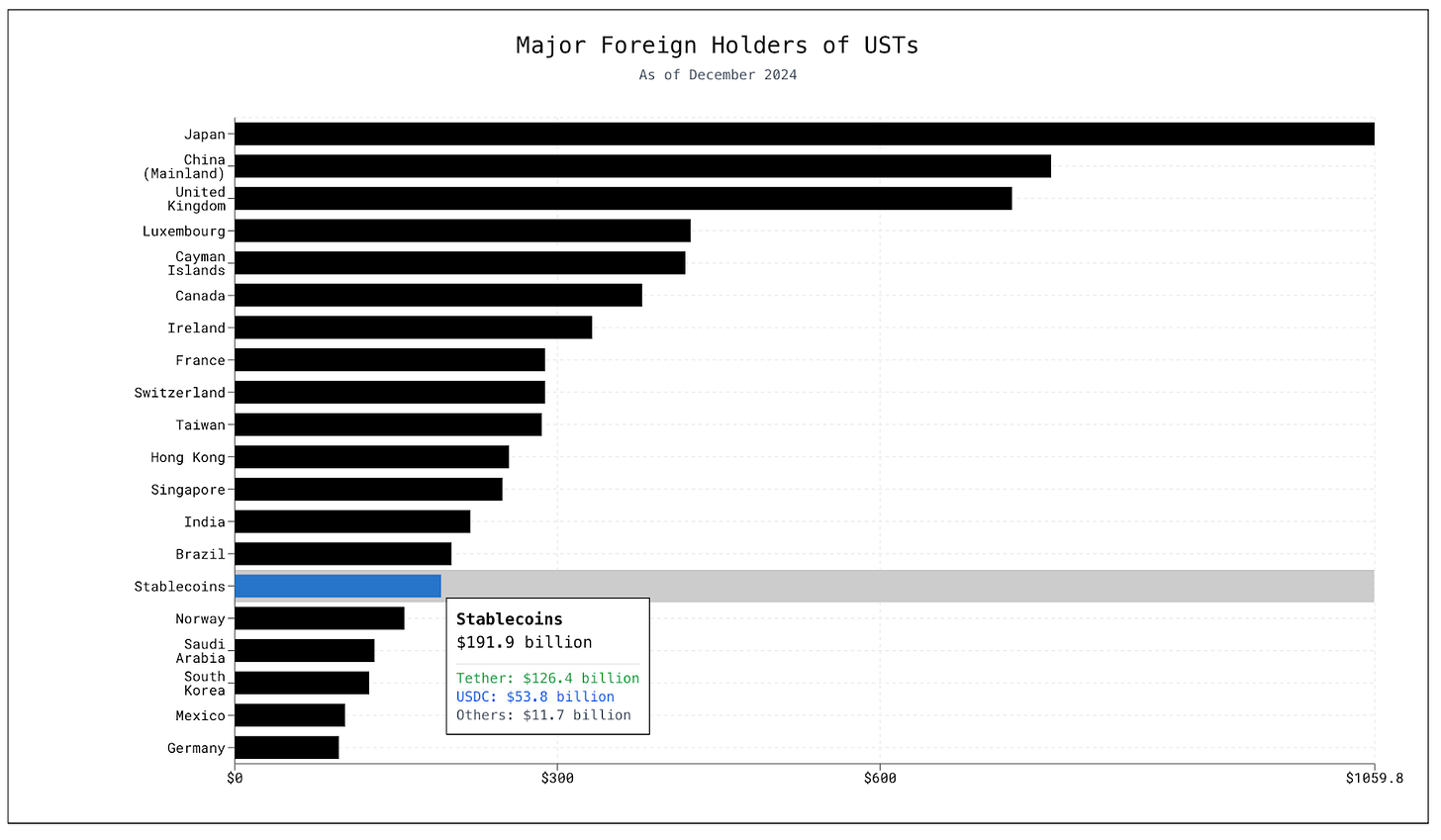

Stablecoins are emerging as powerful instruments of shadow monetary policy, increasingly recognized by governments and treasury departments as strategic tools to manage sovereign debt and proliferate currency and financial system strength around the world.

We project stablecoin market cap to reach roughly $4.9 trillion over the next decade—nearly a 20x expansion from today’s levels.

Introduction

We provide a brief overview of the history of money, the US Dollar, and central banking below. You can skip ahead to the “stablecoin” section if you prefer.

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, and the subsequent government bailouts of over-leveraged financial institutions (“Chancellor on the Brink of Second Bailout for Banks”), Bitcoin emerged as a response: a non-sovereign alternative designed to fulfill the role of “a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash [that] would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.” While Bitcoin successfully functions as a censorship-resistant, bearer asset outside the control of any central authority, it has thus far proven impractical for everyday payments due to a range of limitations, including low transaction throughput, slow settlement times, high fees, price volatility, and a subpar user experience. Although Bitcoin may ultimately prove to be a superior form of money (resistant to fiat debasement and insulated from the whims of central bankers) today, the bulk of global trade is still conducted in U.S. dollars. Increasingly, digital representations of these dollars are filling the role of the electronic cash system that Bitcoin originally set out to replace.

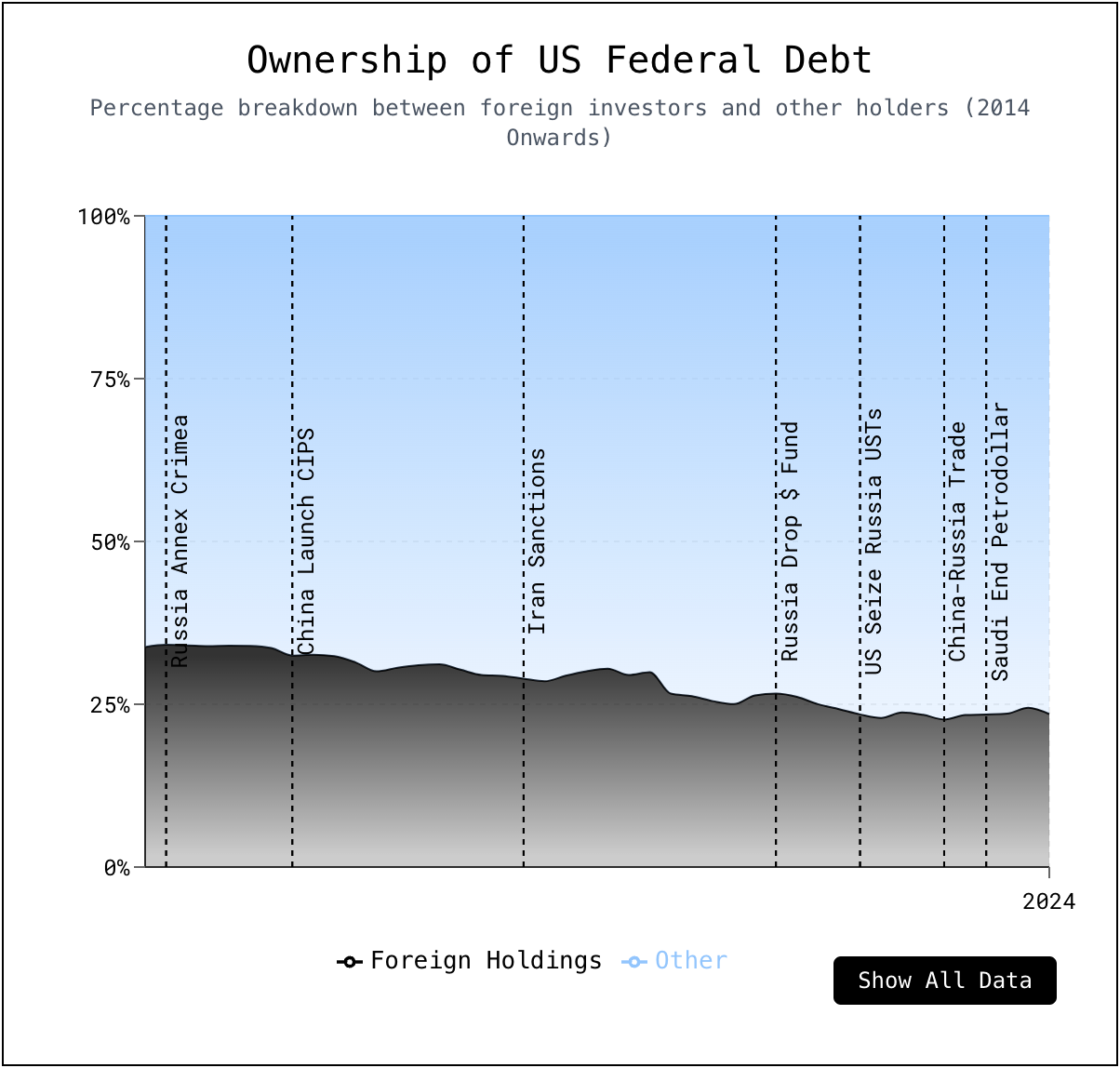

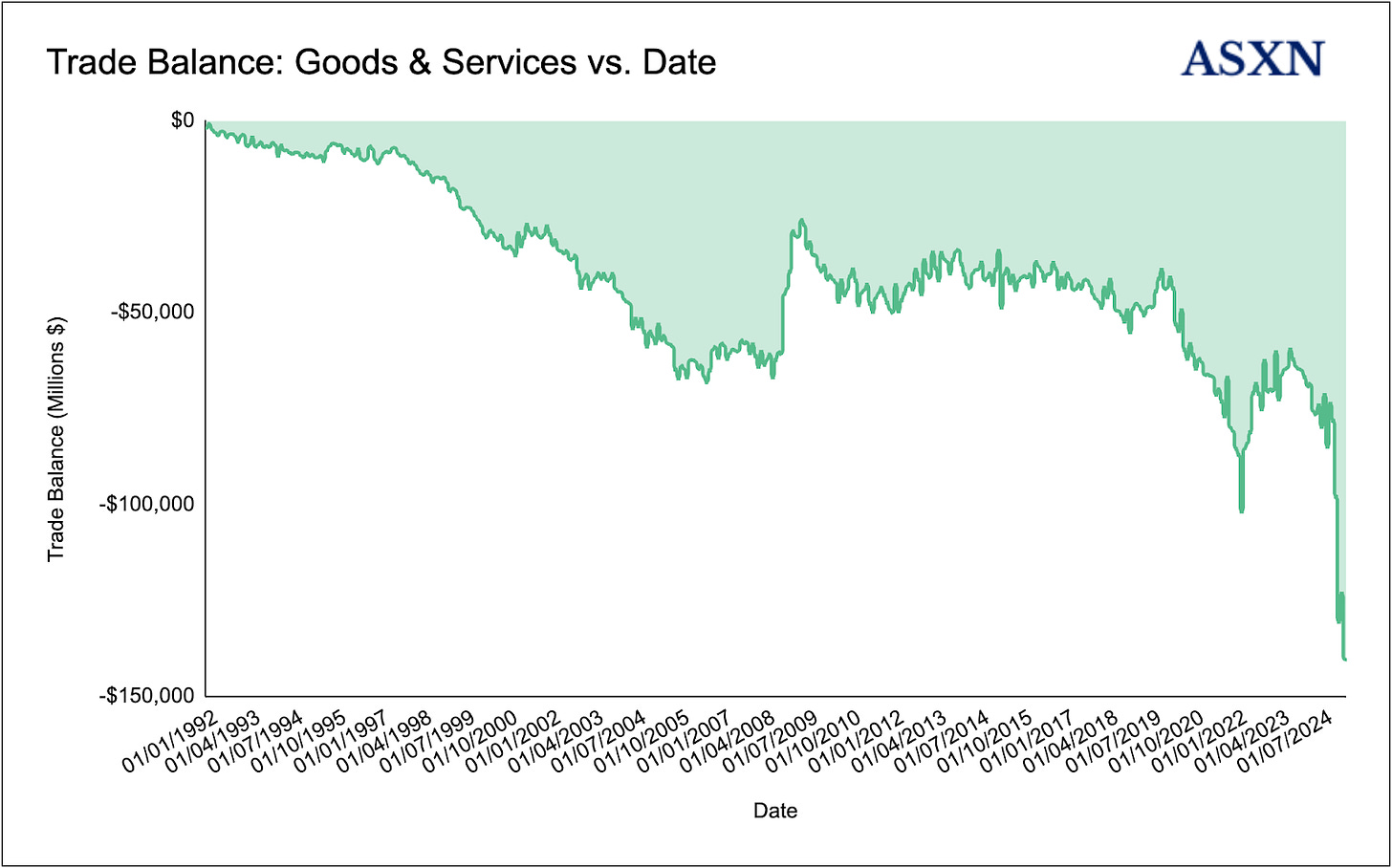

These “room-temperature superconductors for financial services” are proving transformative for individuals in high-inflation or autocratic regimes, by enabling low-cost, peer-to-peer remittance payments. They also enhance user experience and real-time functionality for multinational corporations. Furthermore, we believe the structural debt dynamics of the United States, and the need to identify a new marginal buyer for U.S. Treasuries and preserving the dollar hegemony, combined with the deregulatory stance and macroeconomic policies of the Trump administration, are laying the groundwork for a secular bull market in stablecoin adoption. Under this backdrop, we expect the total circulating market cap of stablecoins to scale well into the trillions of dollars.

The History of Money

To understand why stablecoins represent the future of money and settlement, it's important to first trace the historical evolution of money and identify the core properties that make a monetary system effective in serving society. This includes not only the broader arc of monetary development, but also the emergence of dollar hegemony and the “exorbitant privilege” the United States derives from issuing the world’s dominant reserve currency.

Barter & Commodity Money - Early civilizations relied on barter, the direct exchange of goods and services. As societies grew more complex, barter proved inefficient, leading to the emergence of commodity money such as livestock (9000–6000 BCE) and cowrie shells (circa 1200 BCE in Asia). These early forms of money held intrinsic or socially accepted value, laying the groundwork for standardized mediums of exchange.

Metal Coinage - As trade networks grew, societies increasingly adopted metal for exchange, valued for its durability and ease of division. In China’s Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BCE), early forms of metal money appeared as miniature bronze tools and cast cowrie shell imitations. By the 7th century BCE, true coinage emerged independently in India, China, and the Aegean. Indian coins were punch-marked metal disks, while Chinese coins were cast bronze, often with holes for stringing. In Anatolia, the Lydian kingdom introduced the first standardized coins, stamped to certify their metal content. This marked a major innovation, coinage unified the functions of store of value and medium of exchange, while also allowing states to regulate money supply and profit through seigniorage.The shift from commodity barter to coined money significantly expanded long-distance trade; Athenian silver coins, for example, financed an empire and circulated widely, while Chinese bronze coins helped unify markets across East Asia.

Paper Money & Credit - While coins dominated classical antiquity, the next major leap came in medieval China with the advent of paper money. During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), merchants used promissory notes, known as “flying cash” (飛錢), to avoid transporting heavy copper coins over long distances. This system evolved into a formal paper currency under the Song and Yuan dynasties, giving China over 500 years of early paper money. However, overissuance led to inflation, and by 1455 the Ming dynasty abandoned paper notes due to severe depreciation.Though paper money wouldn’t reach Europe for centuries, China’s experience highlighted both the efficiency and risks of fiat-like currency. Meanwhile, in 12th-century England, the royal Exchequer used tally sticks, notched wooden records of debts and taxes, as a form of credit money. These tallies circulated as “money of account” for transactions with the Crown and remained in use until the 19th century. Together, these innovations marked a shift toward abstract forms of money, written instruments and credit records, laying the foundation for modern banking.

Banknotes, Exchange & Banknotes - By the late medieval and Renaissance period (15th–17th centuries), Europe saw the rise of formal banking and the first paper currencies. Wealthy families like the Medici’s in Florence operated banks that held deposits, extended credit, and pioneered double-entry bookkeeping, laying the groundwork for modern financial accounting. In the 16th century, financial centers like Antwerp and Amsterdam emerged, where bills of exchange, maritime insurance, and international credit supported expanding global trade. A major breakthrough came with the creation of public banks. The Bank of Amsterdam (founded 1609) accepted diverse coins and issued deposit receipts, creating a stable ledger currency or “bank money” widely used in European trade. Merchants could transfer balances directly on the bank’s books, anticipating modern checking accounts. Paper banknotes debuted in Europe in the 17th century. In 1661, Sweden’s Stockholm Banco issued the first public paper money, backed by heavy copper plate deposits. Though initially successful, overissuance led to the bank’s collapse by 1664. In 1694, the Bank of England was founded and began issuing banknotes as receipts for deposits and government loans. These early notes were representative money, redeemable for gold or silver. Over time, the Bank gained a monopoly on note issuance, marking a key shift from private to centralized, state-backed currency systems. This period marked the rise of central banking and national currencies. While medieval money was locally varied, the 17th–18th centuries saw governments begin to centralize and standardize currency. War financing was a key driver, England founded the Bank of England in 1694 to fund its war with France, issuing paper notes in the process. Similarly, colonial America issued paper bills, starting with Massachusetts in 1690, to pay soldiers. Paper money offered clear advantages, lighter, easier to use in large transactions, but relied on public trust, initially maintained through convertibility into gold or silver.

Fiat Money & National Currencies - By the 18th century, paper money and banknotes were common in Western economies, though not always stable. During the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution, governments issued paper currencies not fully backed by specie,an early form of fiat money. The U.S. Continental Congress printed “Continentals,” which quickly lost value due to over-issuance, giving rise to the phrase “not worth a continental.” In the 19th century, national currencies began to take modern form. Many countries established central banks or treasuries to issue standardized notes and coins. Metal-backed banknotes became the norm in peacetime, restoring public trust. In Britain, the Bank Charter Act of 1844 required Bank of England notes,originally private banknotes,to be backed by gold, making them the dominant legal currency. Other nations followed suit, tying their currencies to precious metals to enhance credibility. This marked the beginning of the Gold Standard era.

The Gold Standard - Throughout the 19th century, a central monetary debate revolved around whether to base currencies on gold, silver, or both. Early in the century, many nations operated on a bimetallic standard, recognizing both metals as legal tender. For example, the U.S. Coinage Act of 1792 set a 15:1 silver-to-gold weight ratio. However, as global trade grew and new metal supplies emerged, fluctuations in relative values caused one metal to drive the other out of circulation,an example of Gresham’s Law. Britain led the shift to a pure gold standard in 1816, defining the pound solely in terms of gold and halting high-value silver coinage. Over the course of the century, other major economies followed, and by the late 1800s, gold had become the dominant standard for international trade. The bimetallic debate was especially intense in the United States. After large silver discoveries drove down its value, the U.S. passed the “Crime of ’73”, ending silver dollar coinage and moving the country toward a de facto gold standard. Despite strong populist pressure to restore silver, gold advocates ultimately prevailed. The U.S. formally adopted gold as its sole monetary standard with the Gold Standard Act of 1900. By then, the dollar was officially defined as approximately 1/20.67 of an ounce of gold, solidifying America’s commitment to a gold-based monetary system.

Modern Central Banking and Global Institutions - To manage national currencies and ensure financial stability, countries increasingly turned to central banks. Early examples include Sweden’s Riksbank (1668) and the Bank of England (1694). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, more were established, such as the Bank of France (1800), German Reichsbank (1876), and Bank of Japan (1882). After a long absence of a central authority, the United States created the Federal Reserve in 1913 to address recurring banking panics and regulate credit. Central banks were typically granted exclusive rights to issue banknotes,for example, the Bank of England became the sole legal issuer in the mid-1800s, and the Federal Reserve took on that role in the U.S. after 1913. Under the gold standard, central banks also managed gold reserves and maintained fixed exchange rates, with ensuring convertibility between paper notes and gold being a key responsibility. However, during World War I (1914–1918), many countries suspended gold convertibility to finance war spending by printing money. The United States followed later, abandoning gold for domestic transactions in 1933, amid the depths of the Great Depression.

Electronic Money - The form of money has continued to evolve with advances in technology. In the mid-20th century, banks began using computers, leading to the rise of electronic money transfers. By the 1970s, systems like SWIFT enabled instant global fund movement via electronic signals, replacing the need for physical cash. At the consumer level, payment cards transformed how people accessed money,starting with the Diners Club credit card in 1950, followed by widespread adoption of credit and debit cards in the 1960s–70s. By the late 20th century, most money existed as digital ledger entries, not paper currency. The internet accelerated this shift. By the 1990s and 2000s, online banking and platforms like PayPal enabled anyone to send money electronically. The 2010s saw a surge in mobile payments and fintech innovation, from M-Pesa in Kenya to apps like Alipay and Venmo. Today, most money in advanced economies is entirely digital, with physical cash making up only a small share of the total money supply.

Throughout history and across civilizations, money has independently evolved around a consistent set of fundamental characteristics that enable it to function effectively as a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account. These properties include:

Fungibility: Each unit of money must be interchangeable with another unit of the same denomination. For example, one $100 bill is functionally identical to any other $100 bill, ensuring uniform value and eliminating the need to distinguish between individual units.

Durability: Money must withstand physical wear and tear over time. It should retain its form and function after repeated handling and transactions, ensuring longevity in circulation.

Portability: Effective money must be easy to transport and use across distances. Whether in physical or digital form, it must enable efficient transfer between parties without excessive friction or cost.

Divisibility: Money must be easily divisible into smaller units to facilitate transactions of varying sizes.

Uniformity: All units of the same denomination should be identical in appearance and value. Standardization promotes trust, simplifies recognition, and reduces transaction errors.

Scarcity: To retain purchasing power, money must exist in limited supply. If supply expands too quickly relative to demand, its value erodes, leading to inflation and a breakdown of trust.

Acceptability: Money must be widely recognized and accepted as a valid form of payment. Broad social and institutional acceptance underpins its utility and legitimacy.

Over time, the nature of money has steadily evolved in pursuit of greater efficiency. There has been a persistent drive toward forms of money that transact and settle more quickly, move at lower cost, and operate independently of geographic boundaries,progressing from localized barter systems to global, digital networks.

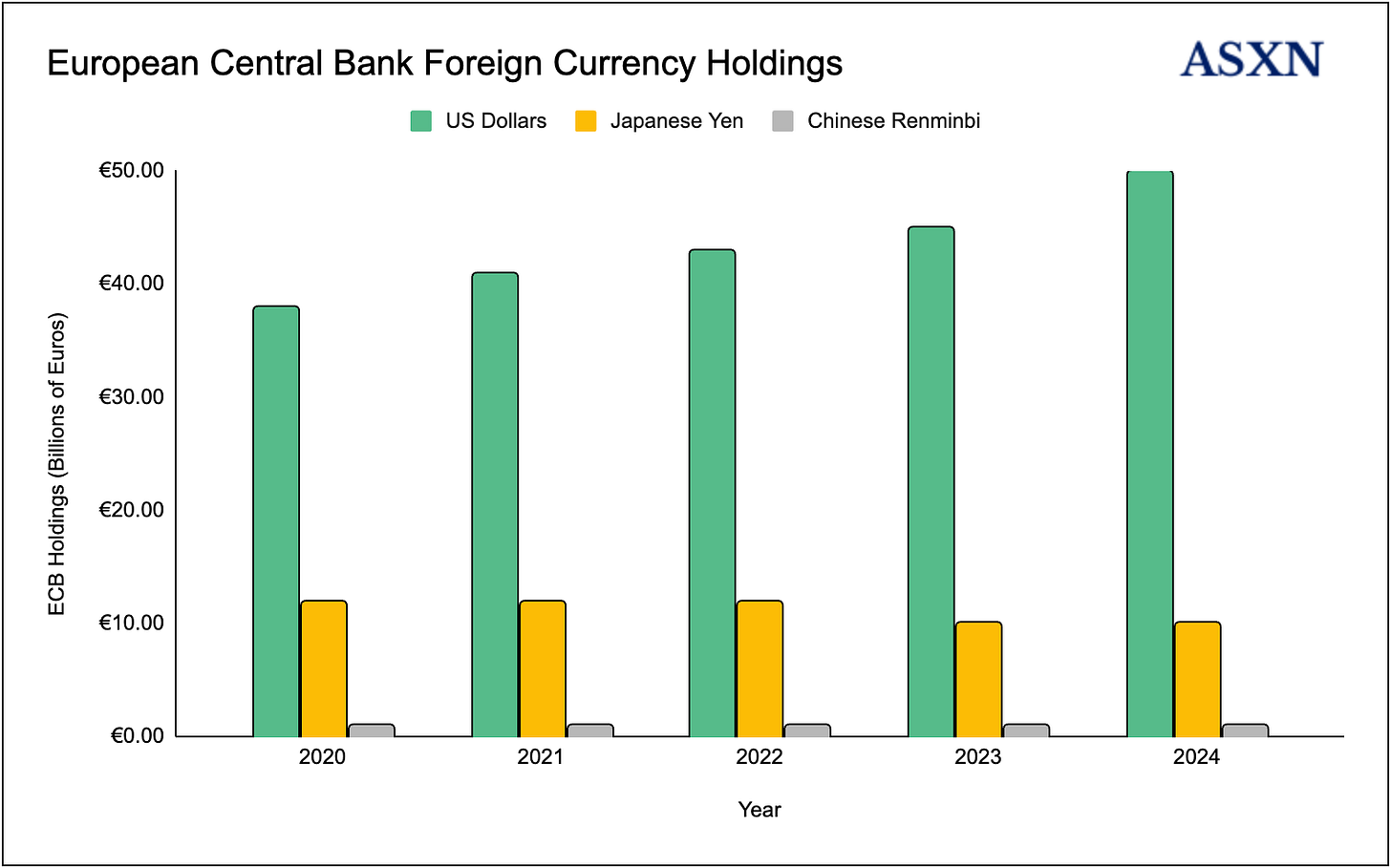

The Dollar Hegemony

Since the end of World War II, the U.S. dollar has emerged as the dominant global currency, meeting the key properties of money more effectively than any other fiat currency. It accounts for approximately 60% of central bank foreign exchange reserves and is used to invoice nearly half of all international trade, even in transactions where neither the buyer nor the seller is American. Being the world reserve currency means that the dollar is the most widely held foreign currency by central banks to fulfill multiple roles including to weather economic shocks, pay for imports, service debts, and moderate the value of their own currencies. Further, most countries want to hold their reserves in a currency with large and open financial markets, since they want to be sure that they can access their reserves in a moment of need. Central banks often hold currency in the form of government bonds, such as U.S. treasuries. The U.S. treasury market remains by far the world’s largest and most liquid, the easiest to buy into and sell out of, bond market.

The United States did not always enjoy the privilege of issuing the world’s reserve currency, nor was its financial system always the most dominant, centralized, and fiat-based, with the deepest and most investable capital markets in the world. The path to that position was marked by a long struggle to establish a national currency backed by a central bank. In fact, the evolution of money in the U.S. bears striking parallels to the current landscape of stablecoins, from the circulation of bank notes during the National Banking Era to the rise, regulation, and controversy surrounding Money Market Funds (MMFs).

We will briefly examine the ascent of the dollar to global hegemony, as this historical context offers important perspective on the secular tailwinds supporting stablecoin adoption, explored in greater depth later in the report. In our view, understanding stablecoins requires more than a technical lens, their trajectory is equally shaped by political and economic forces.

The History of the U.S Banking System & Dollar

Hamilton’s Blueprint (1775 – 1791) - Before the U.S. had a formal banking system, the Revolutionary War and Confederation period left the nation in financial disarray. The war was financed with “Continental” paper currency, which quickly collapsed in value,giving rise to the phrase “not worth a Continental.” To restore order, President George Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first Treasury Secretary. Hamilton proposed federal assumption of state war debts, the issuance of federal bonds, and the creation of a national bank to regulate currency and credit. Disturbed by the chaos of competing state currencies, Hamilton persuaded Congress to charter the First Bank of the United States, calling it “a political machine, of the greatest importance to the state,” and believing it essential to unifying the republic’s financial system.

The First Bank Era (1791 – 1811) - Chartered by Congress in 1791 and signed by President Washington, the First Bank of the United States served as the nation’s first de facto central bank. Headquartered in Philadelphia with $10 million in capital, 20% government-owned and 80% privately held, it acted as the federal government’s fiscal agent, managing deposits, tax collection, payments, and issuing nationally accepted paper currency backed by specie (Gold & Silver). Under President Thomas Willing, it opened branches in major cities and brought stability to the post-war economy. The Bank’s creation sparked intense opposition from Jefferson and Madison, who argued it was unconstitutional and favored elites. Although effective, political resistance grew, and in 1811, Congress narrowly voted against renewing its charter. Without a central bank, the U.S. faced financial chaos during the War of 1812, highlighting the need for a new national institution and setting the stage for the Second Bank of the United States.

The Second Bank & Jackson’s “Bank War” (1816 – 1836) - In response to the financial chaos following the War of 1812, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816 for another 20-year term, with $35 million in capital and headquarters in Philadelphia. Even President James Madison, a former opponent of the First Bank, acknowledged the need for a central financial institution to stabilize the postwar economy. Led later by Nicholas Biddle, the Bank sought to regulate credit and the money supply. However, it became the target of President Andrew Jackson’s populist crusade against centralized financial power. Declaring the Bank a “den of vipers and thieves,” Jackson vetoed its re-charter and withdrew federal deposits, effectively destroying the institution.

Free‑Banking & Wild‑Cat Money (1837 – 1862) - The period from the late 1830s to the Civil War, known as the Free Banking Era, saw banking left to state control after the collapse of the Second Bank. States like New York passed “free banking” laws allowing nearly anyone to start a bank if they met basic requirements and posted bond collateral. With no federal oversight, over 8,000 distinct banknotes circulated, each trading at varying discounts based on the issuing bank’s reputation and distance from redemption. Some banks, known as “wildcat banks,” operated in remote areas to avoid redemptions and issued notes not fully backed by specie, leading to widespread instability and fraud. In places like Michigan, failures were common, and panics in 1837 and 1857 reinforced the public’s desire for a national banking framework and uniform currency.

Civil‑War Finance & the National Banking Acts (1863 – 1879) - The Civil War triggered a financial revolution as the Union scrambled to fund the war effort. Initially relying on bond sales and higher taxes, the North soon faced a cash crunch and, by late 1861, suspended gold convertibility as coinage vanished from circulation. In 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, authorizing $150 million in paper currency known as “Greenbacks”,non-interest-bearing Treasury notes made legal tender but not backed by gold. These fiat notes filled a critical currency gap, though they traded at a discount to gold and fueled inflation. Ultimately, about $450 million in Greenbacks were issued, becoming the first large-scale fiat currency in U.S. history and remaining in use well into the 20th century. Although the system brought stability and financed victory, it also triggered significant inflation,Northern prices rose roughly 80% during the war. After 1865, efforts shifted toward restoring gold-backed currency, culminating in the 1879 resumption of specie redemption at a fixed rate of $20.67 per ounce.

Gold, Populists & Morgan’s Midnight Rescue (1879 – 1907) - With the successful Resumption of Specie Payments in 1879, the United States firmly entered the classical Gold Standard era, pegging the dollar to gold at $20.67 per ounce and making paper currencies,Greenbacks, gold certificates, and national bank notes,freely convertible into gold. Spanning roughly 1880 to 1914, this period was marked by strong economic growth, rapid industrialization, and the U.S. rising as a global economic power. However, it was also plagued by recurring banking panics,in 1884, 1890, 1893, and most dramatically in 1907,highlighting deep structural flaws in the financial system. During these crises, credit and currency dried up, interest rates surged, and banks hoarded reserves, triggering contractions in lending. Clearinghouse associations in major cities attempted to contain the damage by issuing emergency loan certificates, but these ad hoc measures underscored the absence of a formal mechanism to inject liquidity. Meanwhile, political battles over monetary policy intensified, particularly among farmers and debtors in the West and South who, suffering from gold-induced deflation and falling crop prices, demanded the free coinage of silver to expand the money supply. The Panic of 1907, which forced financier J.P. Morgan to personally orchestrate a private-sector rescue,famously locking New York trust company heads in his library until they agreed to a bailout,became the final catalyst. The chaos convinced even Wall Street that the country needed an elastic currency and a true lender of last resort, setting the stage for the creation of the Federal Reserve.

From Jekyll Island to the Federal Reserve (1907 – 1913) - In 1910, Senator Nelson Aldrich secretly convened five prominent financiers on Jekyll Island to draft a plan for a new central bank, operating under first-name aliases to conceal their identities,Paul Warburg later quipped it was “as secret as the Confederate navy.” The result was the Aldrich Plan, a detailed proposal for a central institution with regional branches, a currency backed by both commercial paper and gold to ensure elasticity, and governance dominated by bankers. Aldrich unveiled the plan in 1912, but political tides had shifted: Democrats, long skeptical of concentrated financial power, had won the White House and Congress with Woodrow Wilson’s election. The Aldrich Plan, viewed as too aligned with Wall Street and burdened by its secretive origins, met with resistance. Nevertheless, many of its core ideas were retained. Wilson himself acknowledged the plan was “60–70 percent correct.” Congressional Democrats, led by Congressman Carter Glass and Senator Robert Owen, reworked the proposal, and after considerable debate, Wilson shaped the final version. On December 23, 1913, the Federal Reserve Act was signed into law, establishing the Federal Reserve System,12 regional “bankers’ banks” empowered to issue flexible Federal Reserve Notes and manage the nation’s monetary system.

Fed Formative Years & the Roaring Twenties (1914 – 1928) -The Federal Reserve System began operations just as World War I (1914–1918) erupted in Europe. Although the U.S. remained officially neutral until 1917, the war had immediate economic repercussions. Capital fled war-torn Europe and flowed into the U.S., which became a key supplier of arms and goods to the Allies,financed largely through massive loans. New York’s financial markets expanded rapidly, and the U.S. dollar began to displace the British pound in international transactions. While many belligerents suspended the gold standard to print money for the war effort, the U.S. remained on gold, and gold inflows surged as European nations shipped bullion to pay for American exports. By 1917, the U.S. held a dominant share of global monetary gold, accounting for about one-third of central bank and treasury reserves, which totaled an estimated 11,000–12,000 tonnes globally. Continued inflows throughout the 1920s pushed the U.S. share to roughly 40% by 1930. When the war ended, the U.S. emerged as the world’s largest creditor nation, having financed much of the Allied war effort, and the global financial center of gravity began shifting from London to New York. By the mid-1920s, the dollar had become a serious rival to sterling as a reserve and lending currency. However, growing imbalances loomed: the U.S. had accumulated vast gold reserves and was lending aggressively abroad, while much of Europe remained mired in postwar debt and economic fragility.

Great Depression & New Deal (1929 – 1945) - In October 1929, the long-building stock market bubble burst, triggering the Wall Street Crash and wiping out billions in wealth. This collapse shattered confidence and cascaded into the banking system, where many institutions,exposed through loans against stocks or securities affiliates,began to fail. As nearly 9,000 banks collapsed (about one-third of all U.S. banks), the Federal Reserve failed to act decisively. Its decentralized structure led to internal disagreements, and it prioritized defending the gold standard over expanding credit. Some officials embraced a “liquidationist” stance, believing that weak banks and borrowers should be allowed to fail. The result was a one-third contraction in the money supply, driving deflation, halving GDP, and pushing unemployment to 25%. In response, FDR declared a bank holiday, created the FDIC via the Glass-Steagall Act, and split commercial from investment banking. Through Executive Order 6102, Americans were forced to surrender gold in exchange for dollars at $20.67/oz, effectively nationalizing gold to stop dollar runs and enable monetary expansion. The 1934 Gold Reserve Act ratified this, devaluing the dollar by raising gold to $35/oz. With most of the world’s gold and a stabilized banking system, the U.S. dollar emerged dominant,poised to lead the post-WWII global monetary order.

Bretton Woods (1944 – 1971) - Emerging from WWII with unmatched economic dominance, producing half the world’s output and holding ~70% of official global gold reserves, the U.S. was uniquely positioned to lead the reconstruction of the international monetary system. The British pound had weakened under massive war debts and dollar shortages, and many nations had imposed currency controls. Learning from the failures after WWI and the 1930s devaluations, 44 Allied nations convened in July 1944 at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to establish a new framework. Led by U.S. Treasury official Harry Dexter White and British economist John Maynard Keynes, delegates created the Bretton Woods system, founding the IMF and World Bank and fixing exchange rates with the U.S. dollar convertible to gold. This system effectively formalized the dollar’s central role in global finance,underpinned by U.S. economic strength and gold reserves, a status later dubbed an “exorbitant privilege” for enabling the U.S. to borrow freely and run external deficits. For the next quarter century, Bretton Woods defined international finance until its collapse ushered in the fiat dollar era.

Nixon Shock & the Petrodollar (1971 – early 1980s) - On August 15, 1971, President Nixon unilaterally suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system and severing the final link between the U.S. dollar and gold. This marked the shift to a fiat currency regime, where the dollar, and other major currencies, floated freely and were valued by market forces rather than a metal peg. Despite losing its gold backing, the dollar retained and even expanded its role as the dominant global reserve currency, due to limited alternatives and enduring confidence in U.S. financial markets. A critical development followed the 1973–74 oil shock, when OPEC dramatically raised oil prices, forcing importing countries to secure more dollars to pay for energy. In 1974, the U.S. struck a strategic deal with Saudi Arabia: in return for military protection and arms, Saudi Arabia agreed to price oil exclusively in dollars and to invest its oil revenues in U.S. Treasury securities. This arrangement, soon mirrored by other OPEC members, established the petrodollar system. As oil-exporting nations amassed large dollar surpluses, they deposited them in international banks or reinvested them in dollar-denominated assets,a process known as petrodollar recycling. By 1975, all OPEC countries had adopted dollar pricing, embedding the dollar at the center of global trade and finance. This recycling of petrodollars helped finance persistent U.S. budget and trade deficits while suppressing interest rates, reinforcing the dollar’s dominance and granting the U.S. a renewed version of its “exorbitant privilege.” In the 1970s, money market funds emerged as a corporate cash management tool, offering a stable $1 share price and easy access to short-term instruments. The first (Reserve Fund) launched in 1971 with $1 million in assets.

Deregulation, Globalization & the Eurodollar (1980s – 1999) - During the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. dollar’s dominance solidified amid financial deregulation, the defeat of inflation, and accelerating globalization. Under Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, inflation fell from ~13% in 1980 to ~3% by 1983, restoring confidence in the dollar as a stable store of value. The dollar surged to record highs by the mid-1980s, prompting the 1985 Plaza Accord,where the U.S. and key allies coordinated to devalue the dollar, which subsequently fell ~40% against the yen and mark by 1987, helping to reduce trade imbalances. Financial deregulation, including the 1980 Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act, removed deposit rate caps and broadened access to the Fed’s services, allowing banks to compete more effectively for deposits. In the 1990s, globalization intensified, and the dollar became the currency of choice in expanding global capital markets. The eurodollar market boomed, and by the late 1990s, around 64% of global debt was dollar-denominated, with the dollar comprising 59% of FX reserves and 58% of international payments,cementing its central role in the global financial system.

The Global Financial Crisis & QE (2000’s) - The 2000s tested the U.S. banking system and the dollar, most notably during the 2007–2009 Global Financial Crisis,the worst downturn since the Great Depression. Though the crisis began in the U.S. housing and banking sectors, it paradoxically reinforced the dollar’s global safe-haven status. Hedge funds and mortgage lenders began collapsing in 2007; by March 2008, Bear Stearns failed and was absorbed by JPMorgan with Fed support. The crisis peaked in September 2008 with Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy, freezing interbank lending and triggering runs on money market funds, one of which "broke the buck." Global contagion followed, as many foreign banks held U.S. mortgage securities or relied on dollar funding. The U.S. response was massive: the Fed slashed rates to near-zero, created emergency lending facilities, opened dollar swap lines with foreign central banks, and became a global lender of last resort. The Treasury launched the $700 billion TARP to inject capital into banks and stabilize institutions like AIG. The FDIC guaranteed bank debt and expanded deposit insurance to $250,000. Starting in late 2008, the Fed began quantitative easing (QE), purchasing long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act imposed stricter capital and liquidity rules, while successive QE rounds (QE2 in 2010, QE3 in 2012–2014) helped support a slow but steady recovery and expanded the Fed’s balance sheet to $4.5 trillion.

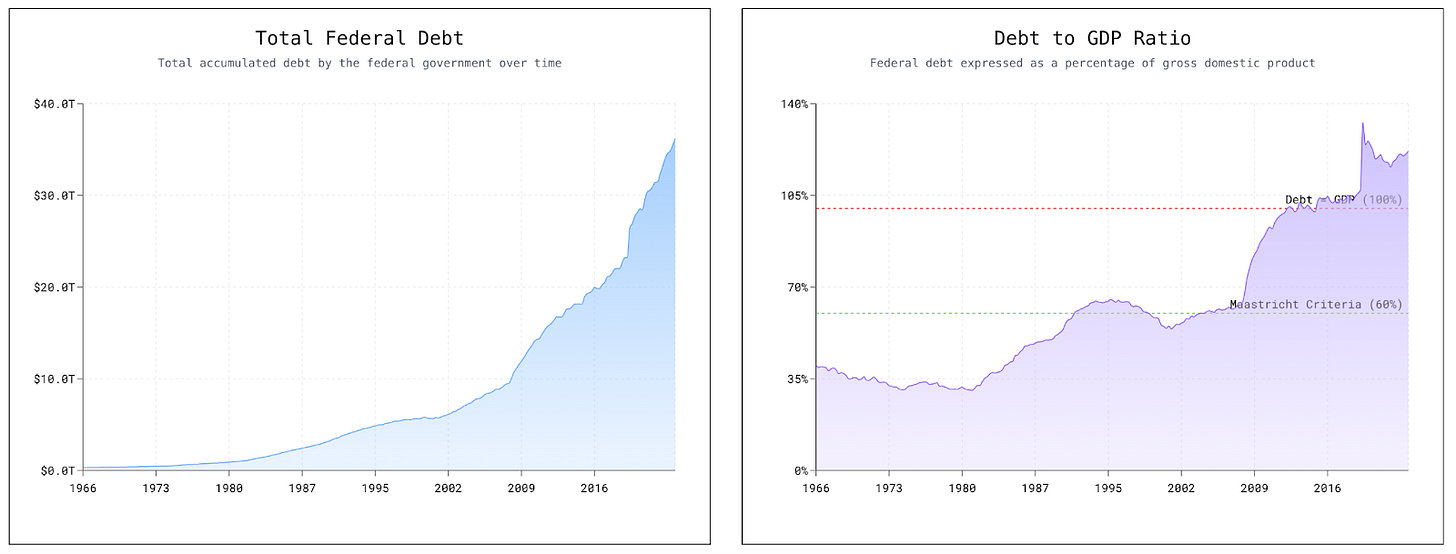

Pandemic QE & De-Dollarization (2010 – 2025) - Over the past decade, the U.S. has seen an extraordinary expansion of monetary stimulus. When QE3 ended in 2014, the Fed’s balance sheet stood above $4 trillion,four times its pre-crisis size. A brief attempt at QT in 2017 was cut short after the 2019 repo-market shock revealed systemic dependence on Fed liquidity. In response to COVID, the Fed slashed rates to zero, restarted QE, and launched emergency facilities, doubling assets to nearly $9 trillion by mid-2022,36% of GDP. Concurrently, over $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus pushed federal debt near 98% of GDP by FY2024. Inflation topping 9% in 2022 forced the Fed to reverse course, hiking rates above 5% and shrinking the balance sheet to $6.8 trillion by early 2025. The dollar still dominates FX markets,used in 88% of trades per BIS,but its share of global reserves has slid from 66% in 2015 to 57.8% by Q4 2024. De-dollarization is gaining traction: Russia’s reserve freeze following the Ukraine invasion raised alarm over dollar risk; Saudi Arabia's decision not to renew the petrodollar pact marked a symbolic shift; Iran increasingly settles trade in non-dollar currencies; and China is promoting renminbi trade settlement, especially amid deepening U.S. tensions since Trump’s tariff war.

Since President Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, the U.S. dollar has operated as a pure fiat currency, freely floating alongside other major currencies. Today, twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks issue a single national currency, Federal Reserve Notes, while the U.S. Treasury mints coins. Nearly all other “dollars” exist as electronic bank deposits settled through the Federal Reserve system.The federal government finances itself by selling Treasury securities into a market that remains the world’s deepest safe‑asset pool: foreigners hold about $8.8 trn of Treasuries, and Japan alone owns $1.13 trn. Persistent global demand keeps yields relatively low,ten‑year notes hover near 4 %,even though publicly‑held debt is now ≈ 122 % of GDP and climbing. That “reserve‑currency dividend” is the flip side of dollar dominance: the U.S. can run large deficits and still borrow cheaply because the rest of the world needs dollar assets for trade, safety and regulation.

Another characteristic of the modern U.S. monetary system is it is now overwhelmingly digital. Of approximately $21 trillion in broad money (M2), around $18.5 trillion, nearly 90%, consists of digital ledger entries maintained by commercial banks or the Fed’s reserve database. Physical currency in circulation totals just $2.36 trillion, and Federal Reserve studies estimate that about 60% of that,especially $100 bills,is held overseas as a portable store of value. Despite the digital nature of money, most retail payments in the U.S. still rely on legacy infrastructure rails such as the half-century-old ACH system, where transfers typically settle the next day,or even two or more days later.

In short, today’s dollar is largely digital, officially singular, fiat‑based and globally coveted, but it moves across a payments grid that is only partially modernised and is backed by a federal balance‑sheet whose size, and future affordability, have become the system’s key long‑term question.

Stablecoin Overview

Stablecoins represent the next phase in the evolution of money and payments, forming the foundation of a financial system with faster settlement, lower fees, seamless cross-border functionality, native programmability and a strong auditability trail. In effect, they wrap the U.S. dollar in software, enabling it to move anywhere the internet reaches,at the speed of light. Put simply, stablecoins are the fastest form of the dollar in existence.

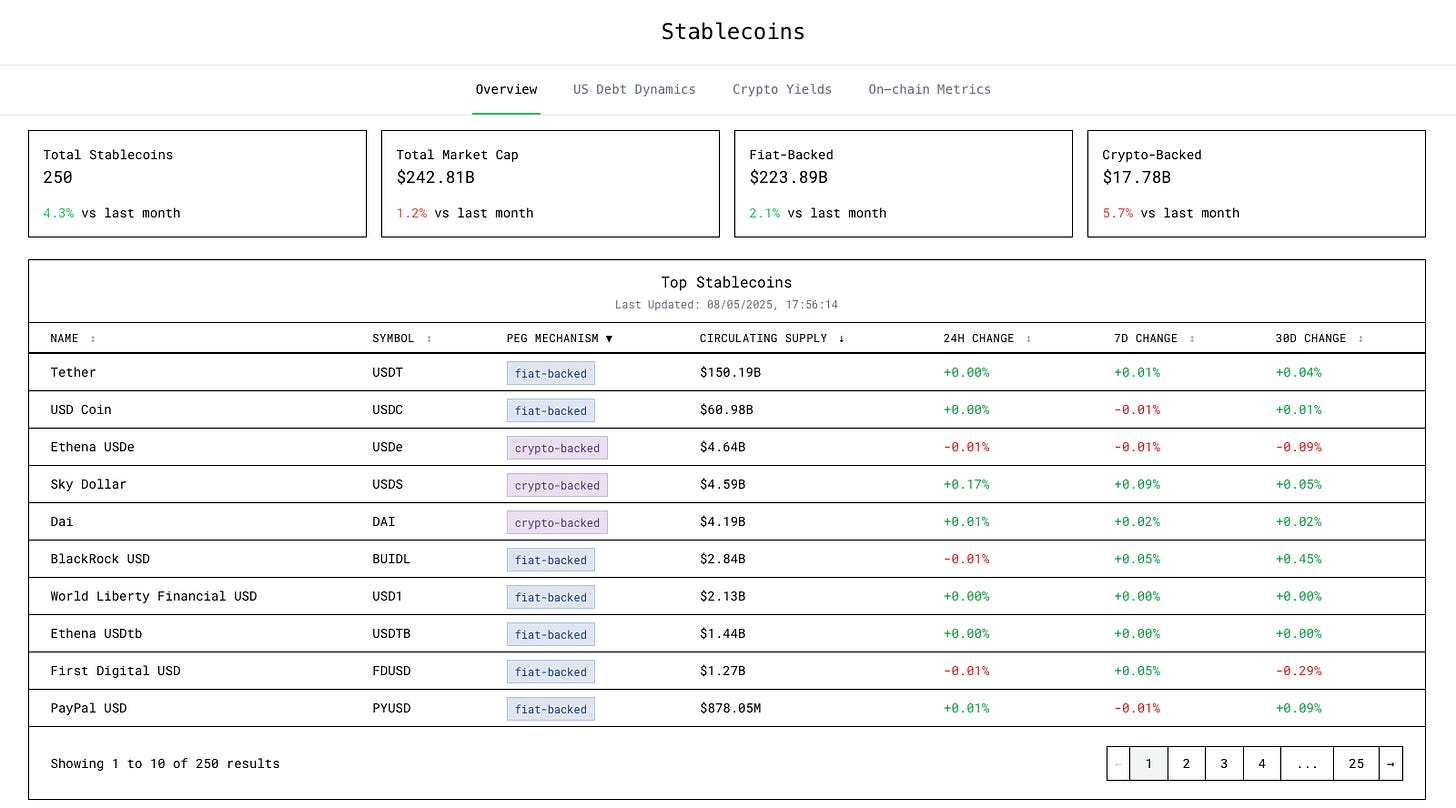

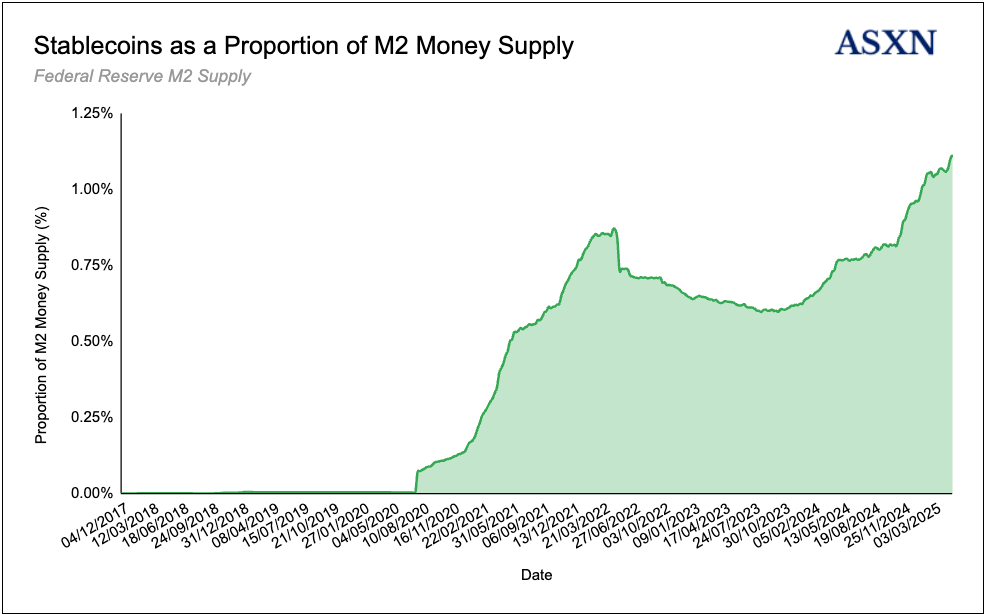

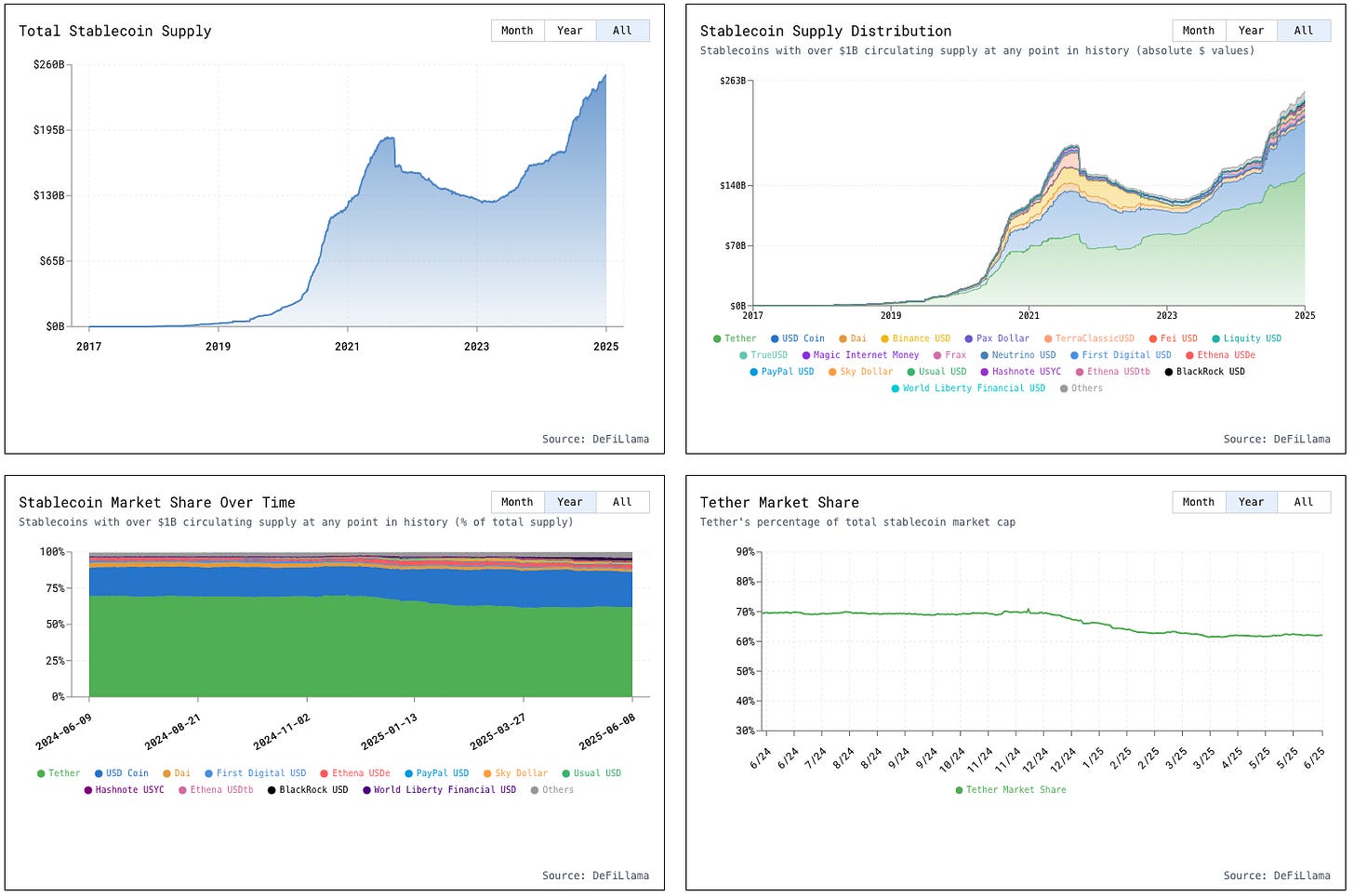

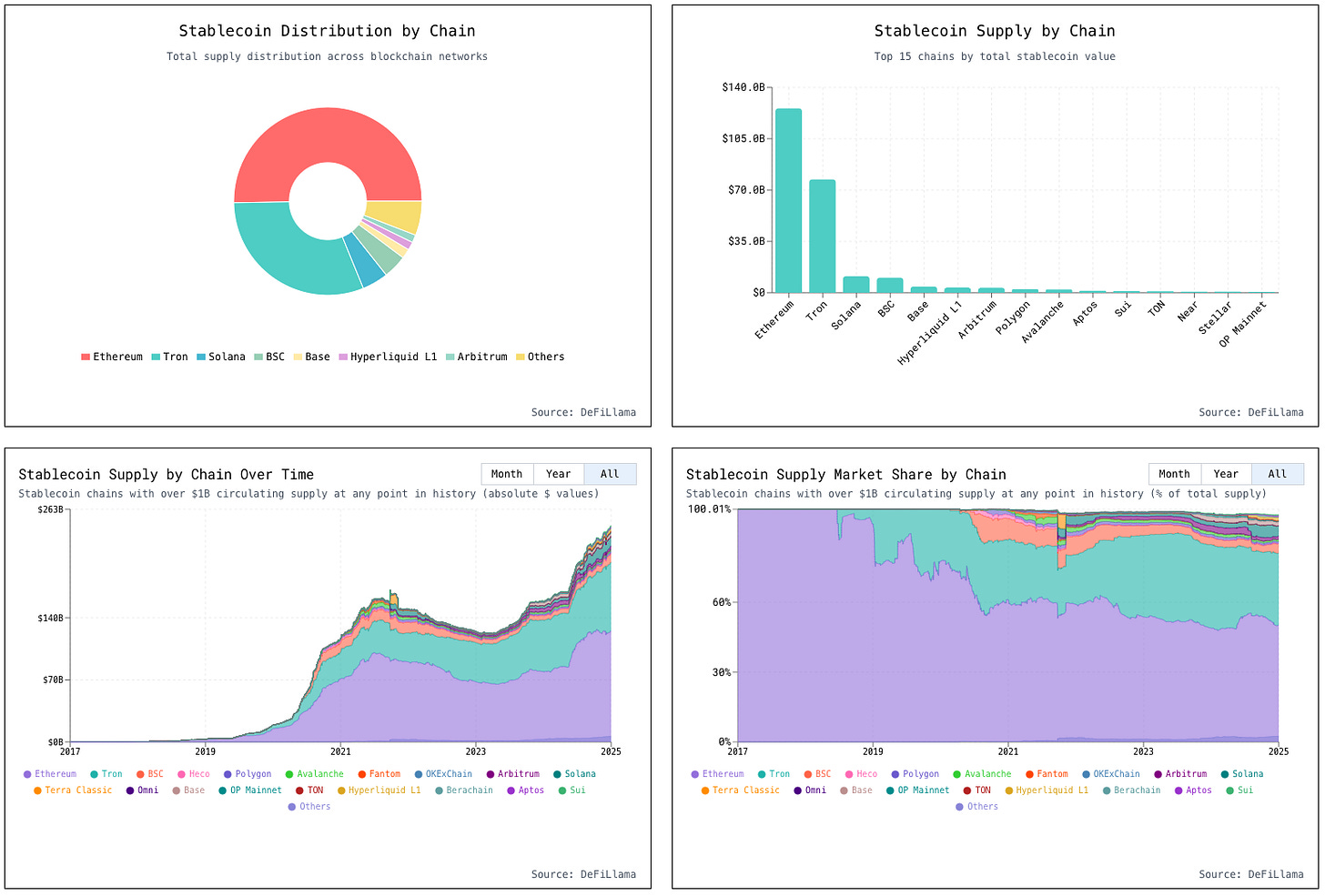

Stablecoins have emerged as the most compelling product-market fit in crypto to date, with their growth trajectory reflecting extraordinary adoption. The market has expanded from just $30 million in total market cap in 2018 to >$250 billion today, representing a 263% compound annual growth rate. Initially used as crypto-native collateral and a settlement mechanism, particularly by market makers and arbitrageurs,stablecoins have since evolved into a broadly adopted financial primitive. Today, trading firms and market makers routinely hold stablecoins on their balance sheets, while DeFi protocols have deeply embedded them into collateral structures and trading pairs. Centralized exchanges are increasingly moving away from BTC-collateralized perpetuals toward stablecoin-based margining. Beyond intra-crypto applications, stablecoins are also gaining traction as a store of value among citizens in high-inflation or politically unstable regions, as well as a tool for fast, low-cost remittance flows. This broader adoption has been enabled by significant improvements in infrastructure,ranging from more efficient on- and off-ramps and high-throughput, low-fee blockchains to better-designed wallets and user-friendly apps built on advances in private key management.

Stablecoin Categories

Today’s stablecoin landscape consists of several distinct types of stablecoin, primarily differentiated by their collateral backing, degree of decentralization, and the mechanism used to maintain their peg. Fiat-backed stablecoins dominate the market, accounting for over 92% of total stablecoin market capitalization. Other categories include crypto-collateralized stablecoins, algorithmic stablecoins, and the more recent emergence of strategy-backed stablecoins. Broadly, a stablecoin is a digital token that maintains a 1:1 value with an established currency, typically the U.S. dollar.

Fiat-backed

Fiat-backed stablecoins mirror the bearer banknotes of America’s National Banking Era (1865–1913): back then, individual banks issued notes that customers could redeem for government-issued greenbacks or specie, and their worth hinged on each bank’s reputation and the holder’s ability to cash them in. Today’s fiat-backed stablecoins promise a one-to-one redeemability with a given fiat currency, but just as 19th-century note-holders relied on secondary markets when they couldn’t reach the issuing bank, modern users depend on platforms like Uniswap or centralized exchanges to swap their tokens for dollars at par (if a direct redeem isn’t possible). This reliable convertibility—enforced by audited reserves and robust trading infrastructure—has fostered the same confidence in fiat-backed stablecoins as widespread redemption assurances did for banknotes over a century ago.

A fiat-backed stablecoin maintains its 1:1 peg by fully collateralizing each digital token with an equivalent amount of fiat currency held off-chain. For example, each USDC token is backed by $1 held in a combination of cash and short-term U.S. government debt. According to current reserve disclosures, each 1 USDC is supported by approximately $0.885 in U.S. Treasuries and $0.115 in cash. The cash portion is held at regulated financial institutions, while the Treasuries, comprising short-dated securities and overnight Treasury repurchase agreements, are custodied at The Bank of New York Mellon and managed by BlackRock.

Typically, select entities can mint and redeem fiat-backed stables. For example, Circle Mint customers, businesses and institutions with verified accounts, can redeem USDC directly with Circle at a 1:1 ratio for U.S. dollars. Redemptions are initiated by sending USDC to the smart contract’s burn function via the Circle Mint dashboard or API, alongside a submitted redemption request. Customers can choose between two options: Standard Redemption, which offers near real-time settlement and is fee-free for amounts up to $15 million per day (with a 0.1% fee on amounts above that), or Basic Redemption, which is entirely fee-free but settles within up to two business days. Once processed, Circle transfers USD to the customer’s linked bank account via ACH or wire, depending on the selected payment rail. This structure supports the 1:1 peg of USDC by enabling arbitrage: when deviations from par occur in secondary markets, traders can capitalize on the discrepancy, helping to restore price stability.

Stablecoin issuers derive most of their revenue from deploying their reserves into interest-bearing US debt instruments. For instance, Tether earned approximately $7 billion in 2024 from holdings in U.S. Treasuries and repo agreements. As a result, stablecoin issuers are incentivized to scale supply, enabling them to invest a larger amount of capital and capture yields that closely track the federal funds rate, currently around 4.25%.

Fiat-backed stablecoins bear a strong resemblance to Money Market Funds (“MMFs”). In the wake of the great depression, the Glass-Steagel Act of 1933 sought to prevent commercial banks from engaging in risky behaviors that had exacerbated bank failures, one such provision, ‘Regulation Q’, capped the interest that banks could offer on deposits. As prevailing market interest rates exceeded the cap on deposit rates, depositors missed out Bruce Bent and Henry Brown launched the first money market mutual fund in 1971, pooling small‐investor cash to buy short‐term commercial paper and repurchase agreements. These funds, unencumbered by Regulation Q’s rate caps (as it was managed by an investment firm), could offer returns that banks simply couldn’t match whilst keeping each share worth $1.

The similarities between fiat-backed stablecoins and MMFs extend beyond structural design. The political and regulatory debates surrounding their oversight echo one another closely. When MMFs first emerged, they faced many of the same criticisms now directed at stablecoins, including concerns over financial stability, insufficient regulation, and the potential for systemic risk:

Financial Stability Risks - Money Market Funds (MMFs) operate without access to federal deposit insurance or central bank backstops, unlike regulated banks. This structural vulnerability makes them prone to liquidity crises and investor runs, as demonstrated during the 2008 financial crisis.

Regulatory Arbitrage - MMFs effectively mimic core banking functions,such as offering a stable, dollar-denominated store of value, while operating outside the stringent regulatory and capital frameworks imposed on traditional depository institutions. This creates a parallel credit system with fewer safeguards.

Monetary Policy Erosion - The growth of MMFs may dilute the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve’s policy toolkit. As assets migrate from the regulated banking system into less regulated vehicles, tools like reserve requirements lose potency, undermining the central bank’s ability to control liquidity and credit conditions.

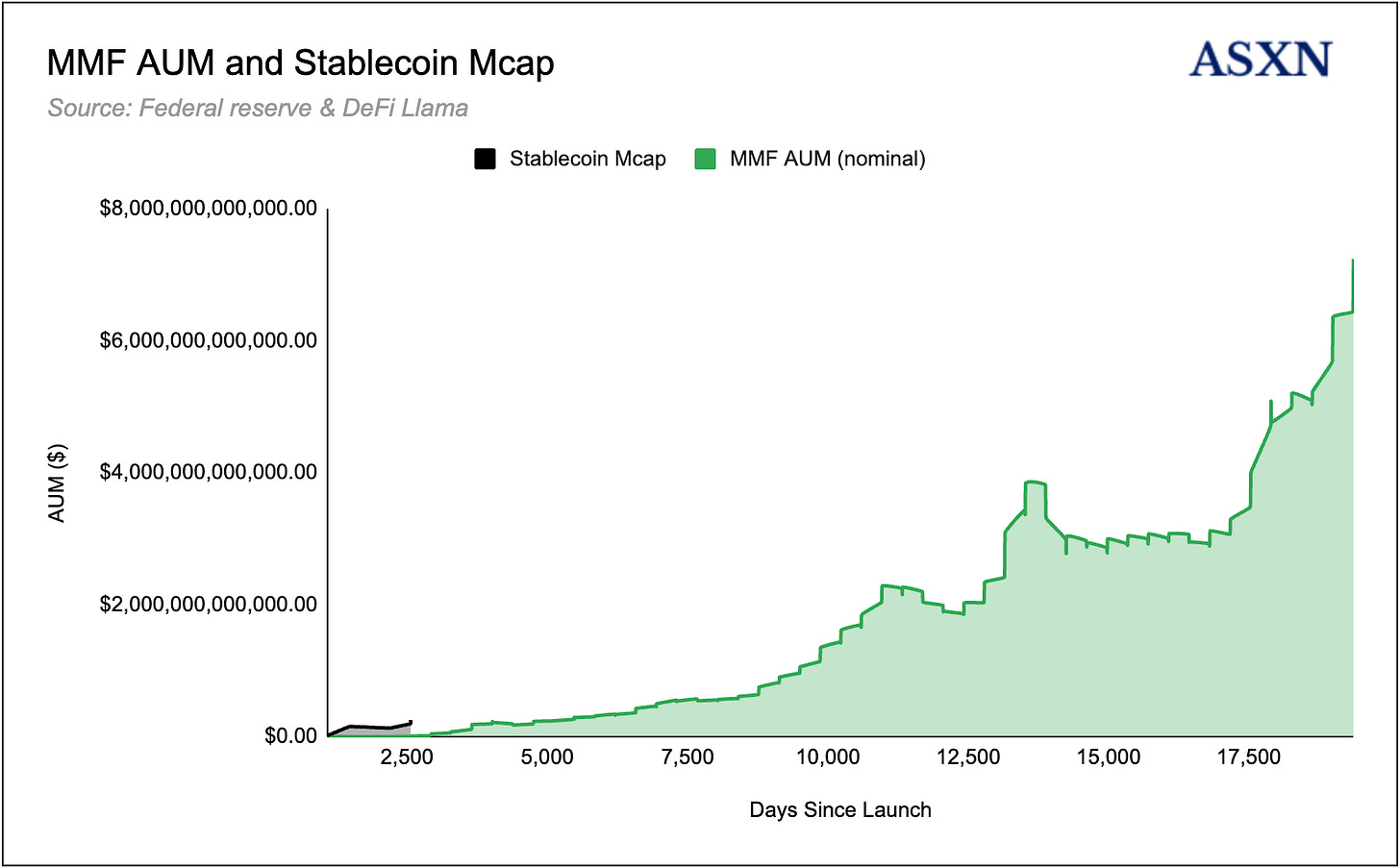

Although MMFs were introduced in the early 1970s, they did not begin to attract significant assets under management until a combination of broad-based financial deregulation, enabling legislation, and key technological advances (such as electronic settlement systems and the internet) laid the groundwork for mass adoption. A pivotal moment came with the passage of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act in November 1999, which repealed key provisions of the 1933 Banking Act and removed long-standing legal barriers separating commercial banking from investment-fund sponsorship and distribution. This regulatory shift allowed banks to fully integrate MMFs into their product suites, making them a seamless part of broader financial offerings. Banks moved quickly to capitalize on these new powers, launching and distributing their own MMFs as part of emerging “financial supermarket” models. By embedding MMFs into core deposit accounts and Treasury-like yield products, banks attracted both institutional and retail investors, who funneled record sums into these vehicles. By the end of 1998, just prior to the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, the U.S. MMF industry had already reached approximately $1.4 trillion in assets. Despite the turmoil of the 2008 financial crisis, MMFs continued to grow, reaching roughly $3.8 trillion in assets under management by year-end 2008. In many respects, their growth pattern parallels the current trajectory of stablecoins, which are similarly benefiting from structural tailwinds and evolving financial infrastructure as we will discuss later.

MMF AUM has now surpassed $7 trillion and continues to grow steadily. In comparison, seven years after their introduction, MMFs had accumulated just $12.8 billion in AUM,or approximately $62.8 billion in today’s dollars when adjusted for inflation. By that metric, stablecoins are already tracking nearly 4x ahead of MMFs at the equivalent point in their lifecycle. Looking at the CPI-adjusted trajectory of MMF AUM, stablecoins appear to be following a remarkably similar growth path. Over the subsequent 15,000 days (roughly 41 years), MMFs scaled their AUM by 55x in real terms, driven by broader distribution, regulatory clarity, and advances in financial infrastructure and technology.

Crypto-Backed

Crypto-backed stablecoins closely resemble the privately issued banknotes of America’s Free Banking Era (1837–1862), which preceded both the National Banking Acts of 1863–64 and the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. In the absence of federal oversight, individual states enacted “free banking” laws that allowed any group meeting modest capital and collateral requirements, usually in the form of state bonds,to charter a bank. By 1860, over 8,000 distinct banknotes circulated, each trading at a discount or premium according to the issuer’s creditworthiness, the cost of physically redeeming the note for specie, and local market conditions. Like today’s crypto-backed stablecoin issuers, these free banks accepted specie (gold or silver coin) and, in some states, short‐term government securities as reserves, then issued their own notes against those reserves while making loans under a fractional‐reserve system.

This same money creation mechanism persists today, which works something like:

A customer deposits $1,000 into their checking account, creating a $1,000 asset (reserves) and a $1,000 liability (the deposit) on the bank’s balance sheet.

Regulators require, for example, a 10% reserve ratio, so on that $1,000 deposit the bank holds $100 in reserve and can lend out $900.

Each time loans are made and redeposited at other banks, the process repeats, multiplying the original base money into a larger total of bank-created deposits. In fact, the majority of broad money (M2) is created this way.

Crypto-backed stablecoins operate similarly but mostly utilise overcollateralized lending systems due to their decentralised / non-KYC nature. Typically, a user deposits collateral,such as $1,000 worth of BTC,into the protocol, which then mints up to $800 in stablecoins, reflecting an 80% loan-to-value (LTV) ratio. To protect the system from insolvency in the event of collateral depreciation, the protocol enforces liquidation thresholds. If the collateral value falls below a specified LTV ratio, the system automatically liquidates the user’s BTC to cover the outstanding debt, thereby preventing the accumulation of bad debt.

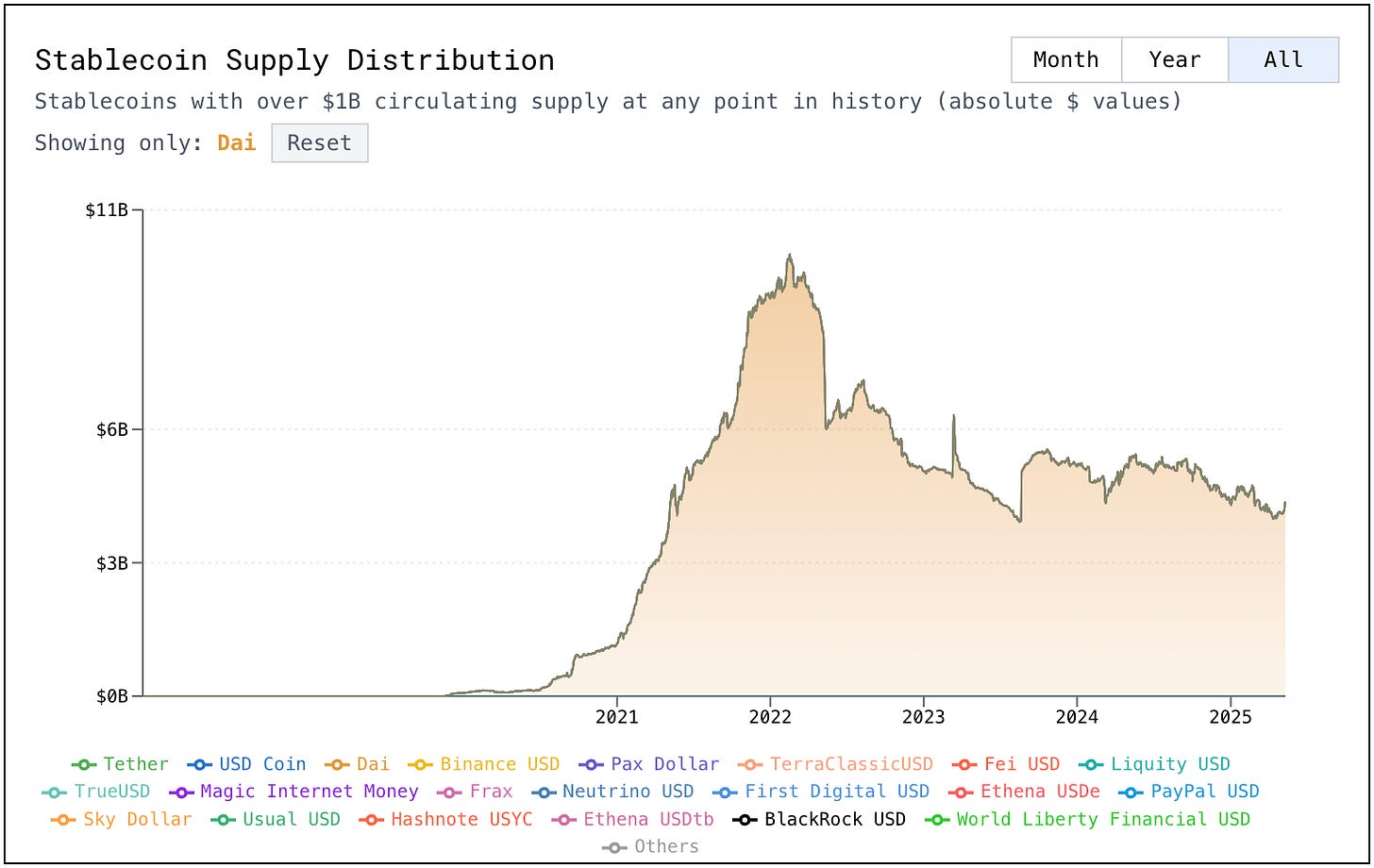

The Maker / Sky protocol issues the largest decentralised crypto-backed stablecoins (DAI & USDS) in the space and has been doing so since the launch of their Single-Collateral Dai in 2017. Users mint Dai by depositing accepted collateral,ranging from crypto assets like ETH, wBTC, stETH, and rETH, to stablecoins such as USDC and GUSD, and tokenized real-world assets including U.S. Treasuries, real estate-backed tokens, and loans,into Vaults (formerly CDPs). Each collateral type is subject to a minimum collateralization ratio (e.g., 150% for ETH), and if a Vault’s value falls below this threshold, it is subject to liquidation to preserve the system’s solvency. The process works as follows:

A user deposits 1 wBTC into a Maker Vault as collateral, worth $100,000. The wBTC Vault type requires a 150% collateralization ratio (66.67% LTV).

The user can then mint a maximum of 66,666 Dai ($100,000 * 66.67%)

If the user mints 50,000 Dai, creating a buffer above the minimum ratio, the vault will now hold 1 wBTC as collateral against a 50,000 Dai debt, with a collateralization ratio of 200% or 50% LTV.

If the value of wBTC falls below $75,000, the Vault collateralization ratio falls above 150% and the vault would become undercollateralized.

At that point, the Vault is subject to liquidation: a portion of wBTC is auctioned / sold to cover the Dai debt, plus liquidation penalties.

If the users wishes to unlock collateral at anytime, the user must repay the 50,000 Dai (plus accrued stability fees), after which they can withdraw the wBTC.

This closely mimics how banks create new money through lending but with liquid, on-chain collateral and each stablecoin is evaluated like the varying banknotes in the free banking era, whereby holders must evaluate the risk of the stablecoin by looking at (non-exhaustive):

The quality, liquidity and volatility of collateral backing the on-chain loans

The protocols ability to safely unwind undercollateralised loans

The security of the smart contracts & mechanism design

For example, during the March 2020 market crash, ETH dropped 53% in two days, exposing major weaknesses in DAI's ETH-only collateral model. The sharp price decline triggered mass liquidations, spiking Ethereum network congestion and delaying oracle price feeds. As a result, DAI lost its peg, trading between $0.96 and $1.13 on March 13. The instability highlighted the risks of relying solely on ETH as collateral, prompting the DAI community to propose adding USDC on March 16 2020 to diversify risk and improve peg stability. Since 2021, DAI has remained relatively stable:

Algo Stablecoins

As opposed to fiat-backed and crypto-backed stablecoins, algorithmic stablecoins are not always backed by hard assets and instead utilise an algorithm and a set of smart contracts to maintain the peg. We can further break down the algorithmic stablecoin category into a few different models for maintaining the peg using Kraken’s analysis:

Seigniorage, or dual-token, algorithmic stablecoins use a two-token system to maintain a stable value. The first token is the stablecoin itself; the second is a bond or utility token used to manage supply and demand dynamics through incentive mechanisms and smart contracts.

When the stablecoin trades above $1, it signals excess demand. In response, the protocol mints new stablecoins and distributes them,typically to holders of the governance or bond token. This increase in supply is intended to exert downward pressure on the price, guiding it back toward the $1 target.

Conversely, if the stablecoin drops below $1, the protocol contracts supply by allowing users to buy bond tokens at a discount (e.g., $0.75). These bonds are redeemable for $1 once the peg is restored. This mechanism both incentivizes buyers and reduces circulating stablecoin, in theory helping to bring the price back to parity.

Terra Luna & the UST stablecoin followed this model with the LUNA token being burned/minted upon price fluctuation to return UST’s value to $1, however, in early 2022 UST lost its $1 peg and the protocol collapsed upon a loss of trust in the system and a highly inflationary LUNA supply that had reflexive effects on the protocol. In just a couple of days, ~$18 billion of value was wiped off the UST market cap as it dropped below sub 10 cents.

The other two broad categories of algorithmic stablecoins are:

Rebasing Stablecoins - Rebasing stablecoins adjust supply directly in users' wallets to maintain a $1 peg. When the price rises above $1, token balances increase proportionally; when it falls below $1, balances decrease. This elastic supply model doesn’t rely on minting or redemption mechanisms. Ampleforth (AMPL) is the best-known example.

Fractional Algorithmic Stablecoins - These stablecoins combine partial collateral backing with algorithmic supply control. A portion is backed by assets like USDC or ETH, while the rest relies on programmatic adjustments. Early versions of FRAX used this model, maintaining a collateral ratio below 100%,e.g., 90% USDC backing.

Since the collapse of Terra Luna and UST, experimentation with algorithmic stablecoins has declined sharply, with many projects,such as Frax Finance and Near Protocol,shifting away from the model. This retreat has been driven in part by regulatory headwinds: a draft U.S. bill proposes a two-year ban on the issuance of new algorithmic stablecoins, while the EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) has imposed a blanket ban. These measures specifically target “endogenously collateralized” stablecoins,those backed by assets native to the same ecosystem. While some experimentation is likely to persist, driven by the appeal of a decentralized and capital-efficient stablecoin, we expect algorithmic models to remain a niche segment. De-peg risks and an increasingly restrictive regulatory environment are likely to limit their role in the future growth of the stablecoin market.

Strategy Stablecoins

A new category of “stablecoins” has recently emerged,tokens that maintain a $1-denominated value while embedding exposure to yield-generating investment strategies. These instruments function less like traditional stablecoins and more like dollar-denominated shares in an open-ended hedge fund. The concept gained attention in March 2023 when Arthur Hayes, founder of BitMEX and a pioneer of the perpetual future contract, published Introducing the NakaDollar. In it, he proposed a hypothetical stablecoin, NUSD, structured as: 1 NUSD = $1 of Bitcoin + Short 1 BTC/USD Inverse Perpetual Swap. Inspired by this idea, Guy Young founded Ethena, which has since become the leading project in this emerging category with its strategy-backed stablecoin, USDe.

Each USDe is minted by depositing an equivalent dollar value of crypto assets (e.g., ETH, BTC, or liquid staking tokens), while simultaneously shorting an equal notional amount through perpetual swaps or futures. This forms a delta-neutral “long + short” basis trade, where price movements in the underlying asset are offset by the short position, keeping the net portfolio value anchored near $1. This structure allows USDe to maintain full 1:1 collateralization without requiring the overcollateralization buffers typical of traditional crypto-backed stablecoins.

USDe is also yield-generating. The short leg of the hedge earns funding payments when perpetual swap funding rates are positive. In this sense, Ethena is effectively providing/funding leverage into the market as there tends to be cyclical but high demand for leverage within crypto. Users can capture this yield by staking USDe to receive sUSDe,the yield-bearing version of the token. sUSDe acts like a savings instrument, accruing yield from funding rates, liquid staking returns, and other protocol revenues, while base USDe remains a non-interest-bearing stablecoin if held idle. In 2024, sUSDe delivered an average annual yield of approximately 19%, reflecting robust demand for leverage and staking rewards in crypto markets.

The launch of Ethena and the success of USDe has spurred on many other strategy-backed stables such as Resolv USD and most recently Neutrl, which is tokenizing access to the OTC arbitrage trade (long discounted OTC rounds, short perpetual) via NUSD.

We refer to these strategy-backed stablecoins as a dollar product, or synthetic dollar product throughout, but it is important to note that they have a different risk profile to what many consider to be a traditional stablecoin (i.e. one that is based on treasury bills or short term government debt instruments). We cover the varying risk models in our report on Ethena which you can find here.

The Case for Stablecoins

Store of Value

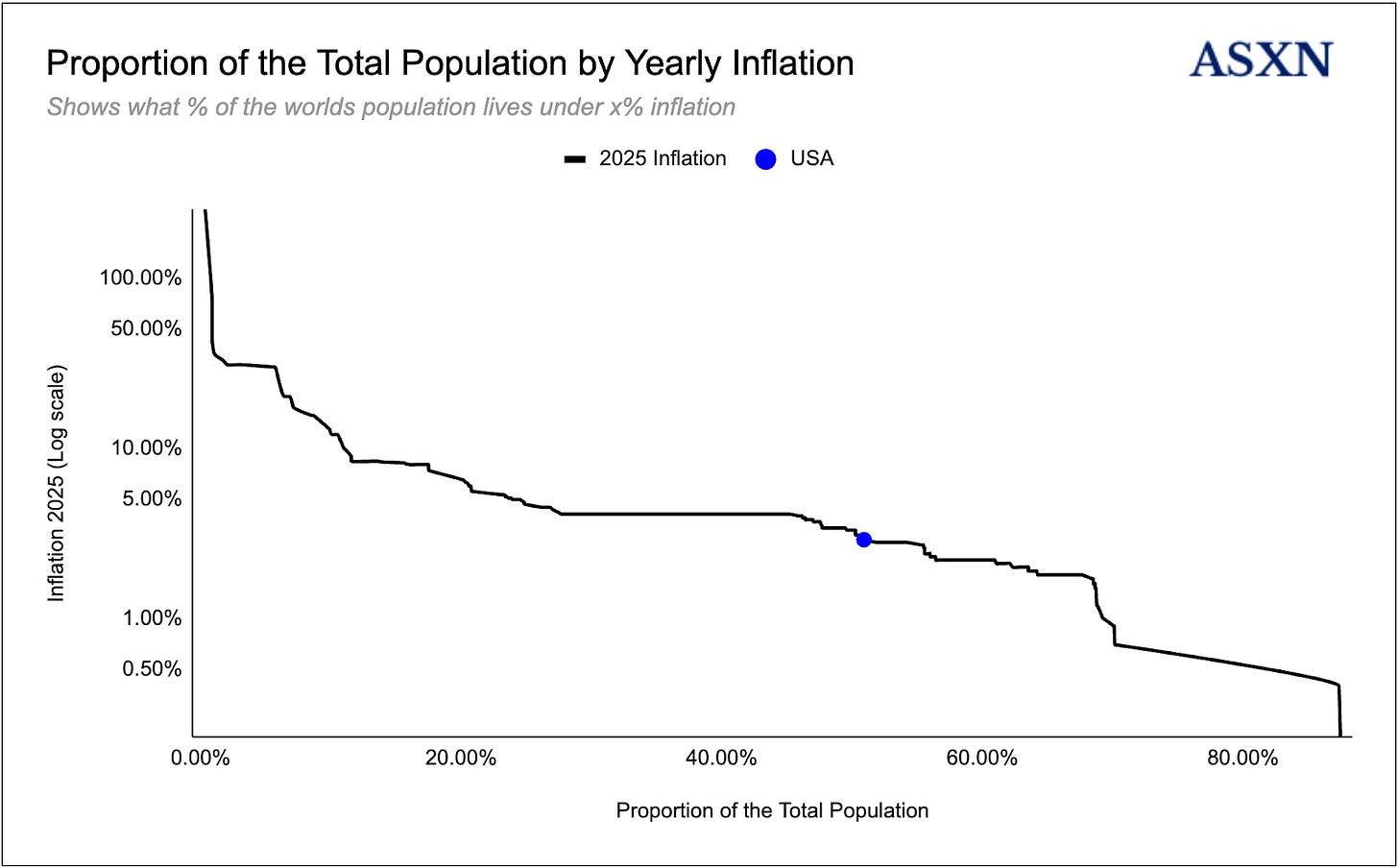

While most investors, particularly those in Bitcoin, recognize that the U.S. dollar is slowly losing purchasing power due to persistent inflation and currency debasement, as Ray Dalio aptly puts it, “the dollar is still the least dirty shirt in the hamper.” In fact, over 20% of the global population lives under regimes experiencing inflation rates of 6.5% or higher and over 51% live with worse inflation than in the USA (in 2025). In countries grappling with runaway inflation, weakening currencies, or strict capital controls, a grassroots financial shift is underway: individuals and businesses are increasingly turning to USD-pegged stablecoins as a store of value. Rather than hold rapidly depreciating local currencies, people in economies like Argentina, Turkey, Lebanon, Venezuela, and Nigeria are parking savings in digital dollars such as USDT, USDC, or DAI. In these environments, stablecoins function less as payment rails and more as digital savings accounts,offering a more stable alternative for preserving purchasing power.

A currency’s effectiveness as a store of value hinges on a few core economic fundamentals. When these underlying factors deteriorate, confidence in the currency erodes over time. Key drivers include:

Inflation - Low and stable inflation is critical for a currency to hold its value. High inflation quickly erodes purchasing power.

Monetary Policy - If markets believe a central bank lacks discipline or independence – for example, if it prints money to finance deficits or pursues unorthodox policies – the currency’s value can plummet. Turkey illustrated this: despite 40%+ average inflation, the central bank cut interest rates in 2022– 2023, undermining credibility and contributing to a 300% loss in the lira’s value over 2020–2023.

Fiscal Discipline - Unsustainable fiscal policy can lead to currency debasement. If a government runs chronic deficits and accumulates debt that investors doubt can be repaid, it may resort to monetizing the debt (i.e. printing money). This expands the money supply and fuels inflation, impairing the currency’s value. Lebanon’s government debt default and deficit monetization in the late 2010s, for instance – experienced currency collapse and triple-digit inflation

Money Supply - Closely related, the rate of money supply expansion relative to real economic growth impacts long-term value. If the money supply grows far faster than the economy (often the case when central banks finance government spending or bail out banks), inflation and depreciation usually follow. For example, Venezuela’s broad money supply skyrocketed during its hyperinflation period, contributing to the bolívar’s collapse as a store of value.

Capital Controls & Convertibility - A currency’s value storage appeal also hinges on the ability to freely convert or transfer that value. When governments impose capital controls – limiting foreign exchange access, restricting cross-border transfers, or fixing unrealistic exchange rates – the currency becomes “trapped” and often overvalued domestically. This undermines confidence because people fear they can’t exit into a stable asset when needed.

Political & Institutional Stability - Finally, broader political risk factors play a role. Regime instability, the threat of expropriation or bank freezes, and lack of rule of law all reduce confidence in local currency and banks. A dramatic example was Lebanon’s banking crisis: banks imposed informal capital controls and froze deposits in 2019–2020, shattering trust in holding wealth in local institutions

For many countries,and indeed, the majority of the global population,the U.S. dollar serves as a superior store of value. This is largely due to its relative strength across key dimensions: lower inflation, fewer capital controls, and greater political stability. In addition, the dollar offers access to the world’s most liquid financial markets, underpinned by a (mostly) disciplined Federal Reserve that operates with explicit targets around core economic indicators.

We can take a closer look at some case studies of how citizens in emerging economies and how they are utilising stablecoins to protect their wealth:

Argentina

Argentina is a textbook example of capital flight to stable value via crypto. Decades of chronic inflation and recurring currency crises have eroded public trust in the peso. While current inflation stands around 20%, the country endured a staggering 143% inflation rate in 2023, driving roughly 40% of Argentinians into poverty. In December 2023, newly elected President Javier Milei devalued the peso by 50%,a move he called “shock therapy”.

“To protect themselves from this economic crisis, some Argentinians have turned to the black market to acquire foreign currencies, most commonly the U.S. dollar (USD). This “blue dollar” is the U.S. dollar traded at a parallel, informal exchange rate, often purchased through clandestine exchange houses called “cuevas,” found throughout the country. Others have explored USD-pegged stablecoins, which is reflected in our data.

We looked at monthly stablecoin trading volume with the ARS on Bitso, a leading regional exchange in Latin America, and saw that the peso’s decreasing value consistently sparked an increase in monthly stablecoin trading. For instance, when the ARS’s value fell below $0.004 in July 2023, the monthly stablecoin trading value surged to over $1 million in the following month. Similarly, when the ARS’s value dropped below $0.002 in December 2023 , when President Milei made his announcement , the stablecoin trading value exceeded $10 million the following month.” - Chainalysis.

USDT is widely used for everyday transactions in some circles, effectively acting as a parallel currency. Even Argentina’s tax authority has taken notice – one province (Mendoza) began accepting stablecoins for tax payments in 2022, legitimizing their role as money in practice. For the average Argentinian, stablecoins represent a lifeline: a way to hold “dollars” that won’t melt away in value, accessible without special permission.

Lebanon

Lebanon’s financial collapse, which began in 2019, illustrates why ordinary citizens turn to stablecoins when traditional financial systems break down. The Lebanese pound (LBP) lost over 98% of its value during the crisis, wiping out personal savings and driving inflation above 200% by 2023. At the same time, banks froze U.S. dollar accounts and imposed arbitrary withdrawal limits,effectively enacting capital controls that cut depositors off from their own funds. Amid this financial paralysis, many Lebanese turned to crypto assets, particularly stablecoins, as a functional substitute for dollars.

Tether USDT quickly gained traction in Lebanon, becoming a de facto quote currency among local money-changers and dealers,effectively forming a crypto-based parallel exchange market. One report described USDT as “the bureaux de change crypto of choice for dodging banking restrictions.” Its peer-to-peer transferability allowed users to bypass the frozen banking system and official currency peg, trading pounds or other crypto for USDT via Telegram groups or local brokers. Once in USDT, users held a stable store of value shielded from hyperinflation, with the added ability to make online purchases or transfer funds abroad,both otherwise blocked by capital controls.

Lebanon also highlights the trust advantage of stablecoins, particularly when paired with self-custodial wallets. With domestic banks widely seen as insolvent and untrustworthy, storing funds in a personal crypto wallet offered users a sense of control and security. Many Lebanese treated stablecoins like digital savings accounts, holding USDT or USDC for weeks or months and converting to LBP only at the moment of spending.

Stablecoins as a Store of Value

For brevity, we’ve included only select case studies, but Chainalysis offers a great overview of similar trends across Latin America. Broadly speaking, dollar-denominated stablecoins (e.g., USDT, USDC, DAI) hold strong appeal in high-inflation, capital-restricted economies. Several factors make them an attractive store of value:

Preservation of Purchasing Power - For someone in Argentina or Nigeria, moving from a currency losing 20–100% of its value annually into a USD-pegged stablecoin offers instant dollarization and halts purchasing power erosion. Even with U.S. inflation around 3–4%, the contrast is stark. Stablecoins inherit the dollar’s relative stability and credibility,an appealing alternative in countries where trust in local currency has collapsed.

Self-custody - Users self-custody the cryptographic keys of their addresses, meaning their assets aren’t subject to a local bank’s solvency or a government’s freeze order. This is a powerful proposition in places where banks might be bailed-in or withdrawals arbitrarily limited (Lebanon, Nigeria, etc.). With stablecoins, a user can store $100 or $100k on a secure hardware wallet or even a paper backup, and no local authority can devalue or seize it without also somehow compromising the global crypto network.

Liquidity - Holding stablecoins isn’t just about passive saving; they are also highly liquid and usable for transactions. This makes them functionally useful in daily life. Traditional dollar exposure methods (like offshore accounts or physical cash) cannot match that fluidity.

Censorship Resistance - Traditional dollar avenues (banks or remittance services) are subject to surveillance, censorship, or political interference. Stablecoins, especially when transacted on peer-to-peer or decentralized platforms, can offer greater privacy and resistance to censorship.

For these reasons, it is no surprise we are seeing a rapid growth in stablecoin activity, especially in the LATAM and African countries which saw over 40% YoY growth in stablecoin activity as judged by transfers under $1M and Chainalysis’ de-anonymizing software.

Remittance

Remittances represent a major use case for stablecoins. Each year, tens of millions of workers send a portion of their wages back home, supporting over 200 million recipients globally. In 2024, total remittance flows reached approximately $905 billion, a figure comparable to the GDP of a mid-sized developed economy. Continued growth is expected in 2025. A substantial share of these flows, around 76 percent or an estimated $685 billion, went to low and middle income countries (LMICs), where remittances often serve as a financial lifeline. In many of these regions, remittance income covers essential needs such as food, education, and healthcare, underscoring its critical role in household welfare.

As noted, remittances are heavily concentrated in LMICs, where they can account for a significant share of national GDP. Yet these same countries often face the chronic store-of-value challenges we touched on earlier, including weak local currencies, capital controls, and political instability. This makes cross-border inflows particularly vulnerable to value erosion—creating a strong case for stablecoin adoption as a more resilient and efficient alternative.

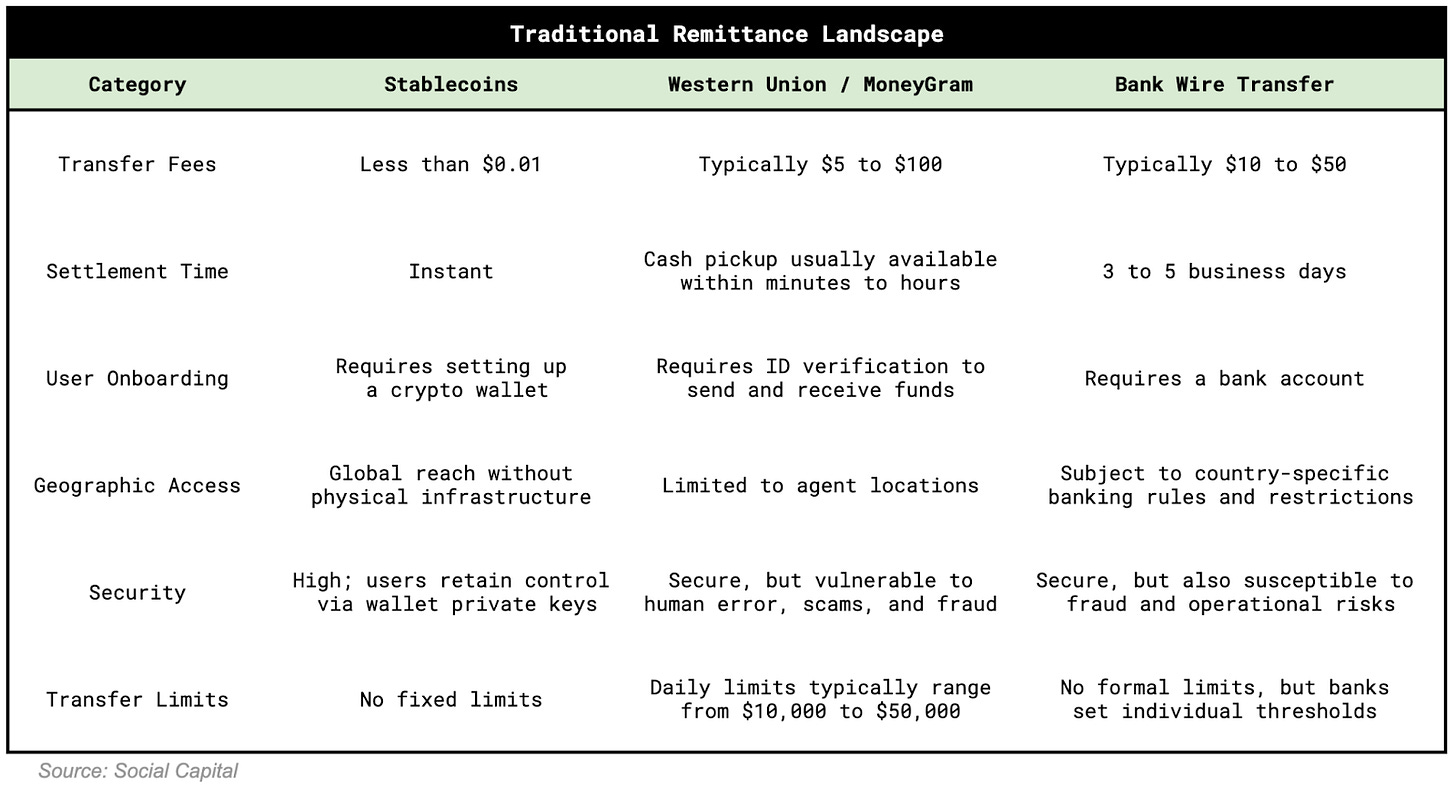

Stablecoins are well suited for remittances not only because they provide a more stable store of value, especially when pegged to the US dollar, but also because they offer faster, cheaper, and more secure cross-border transfers. Currently, most remittances are sent through traditional banks, money-transfer operators such as Western Union and MoneyGram, or mobile-money platforms like M-Pesa in select regions. While these channels are widely used, they often involve high fees and delayed settlement. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the average cost to send $200 abroad was approximately 6.4 percent. In some corridors, that number exceeded 10 percent. For people already managing tight budgets, losing such a large portion of a remittance to fees can be a significant burden. These costs act like a regressive tax on some of the world’s poorest workers and despite the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal of reducing global remittance costs to 3 percent, fees have continued to rise, increasing by 3.2 percent year over year.

Among the primary remittance channels, banks remain the most expensive, with an average cost of 12 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023. Post offices followed at 7.7 percent, money transfer operators averaged 5.5 percent, and mobile money services were the lowest at 4.4 percent. Despite being the most cost-effective option, mobile operators account for less than 1 percent of total remittance volume. In addition to high costs, traditional remittance methods often involve delays. Recipients may wait two to five business days for funds to clear, as payments are routed through multiple correspondent banks. Along the way, hidden fees and unfavorable exchange-rate markups further reduce the final amount received.

Stablecoins for Remittance

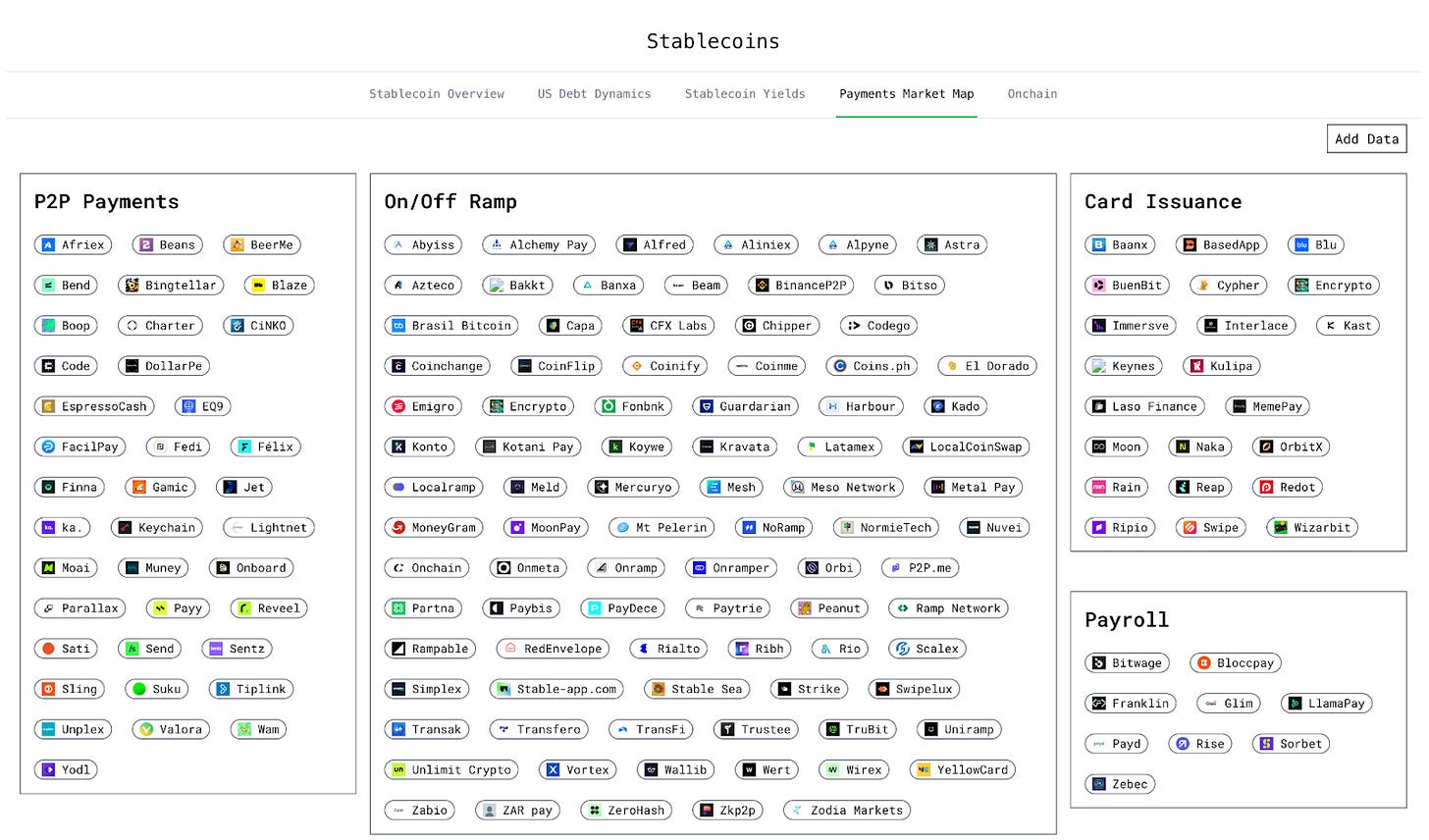

Stablecoins and the crypto rails they run on offer an internet-native alternative for moving money, optimized for speed, transparency, and low cost. Just as the internet revolutionized information by enabling it to travel globally at the speed of light, stablecoins are doing the same for value transfer. Because they operate on public blockchains, transactions settle in seconds rather than days and are available 24/7, 365 days a year.

While the global average fee for remittances is 6.4%, on-chain transaction costs are typically measured in cents or even fractions of a cent, thanks to recent advancements in blockchain scalability. For example, Base has seen median transfer fees average just $0.00024 over the past two weeks, compared to Ethereum’s $0.155. High-throughput blockchains like Solana and soon Plasma promise to push costs even lower, with Plasma aiming for zero transfer fees on USDT transactions.

On top of that the entire payment path is visible on the ledger. No banking relationships or pre-existing accounts are needed: anyone with an internet connection and a digital wallet can send or receive stablecoins, opening access in regions with limited or underdeveloped banking infrastructure. A sender can on-ramp via debit card or bank transfer into USDC or USDT, transmit those tokens across borders almost instantly, and off-ramp into local currency through a network of local partners. Even when off-ramp fees are factored in, now often as low as 0–2 percent in competitive corridors, the total cost frequently falls below 2 percent of the transaction. This reduction in both time and cost represents a dramatic improvement for families who rely on remittances to make ends meet.

Payments

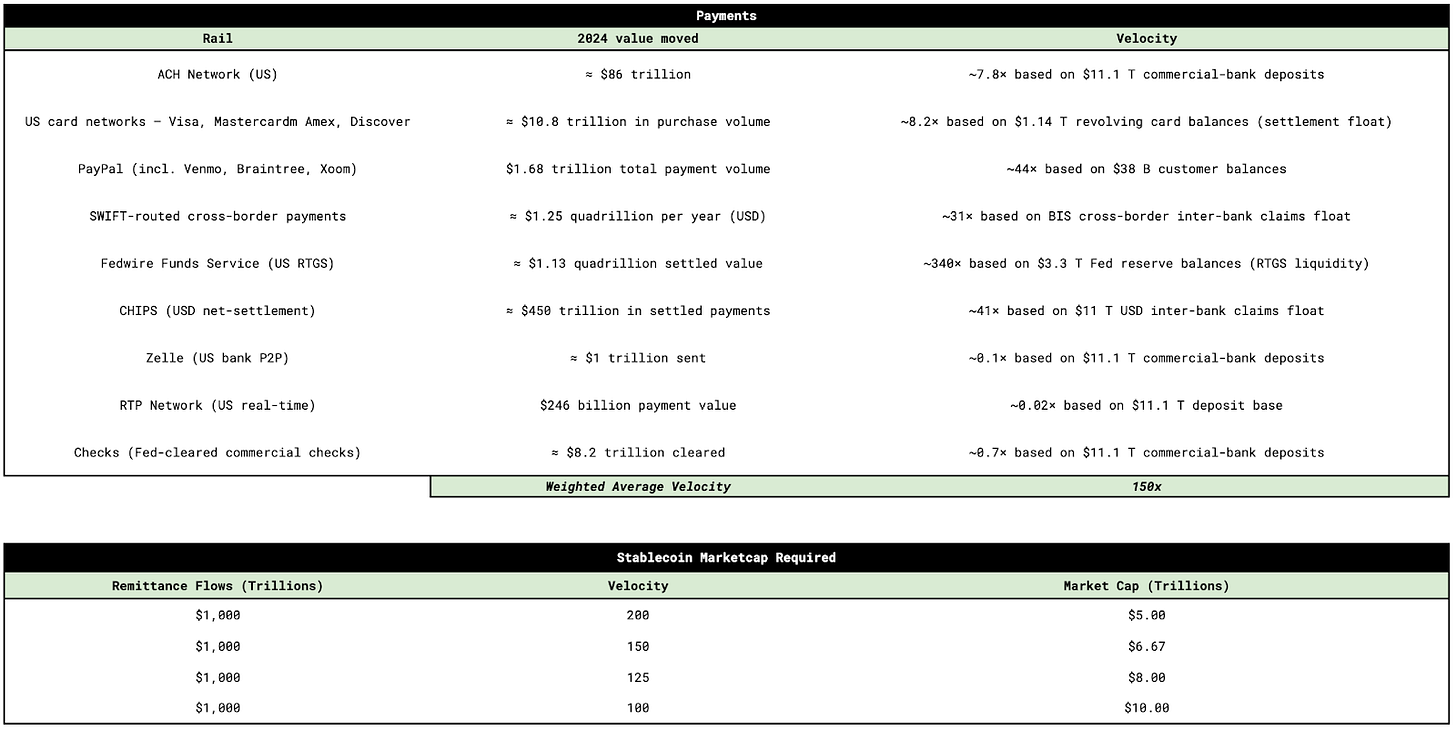

While remittances form a distinct subsegment, the broader global payments ecosystem—which spans consumer-facing transactions, business-oriented flows, public-sector and social disbursements, as well as emerging and embedded rails—continues to grapple with legacy infrastructure. Core limitations such as high costs, slow settlement times, limited transparency, and poor composability persist across all segments. Yet despite these structural inefficiencies, the global payments industry remains one of the largest in the world, processing 3.4 trillion transactions in 2023, representing $1.8 quadrillion in value and generating $2.4 trillion in revenue.

If we take a brief look at the most common payment rails used today, we can begin to see how stablecoins and crypto rails can reduce fees and settlement times and therefore improve the bottom line and functioning of business around the world:

Card Networks - Card networks and payment cards trace back to the 1950 launch of the Diners Club charge card and have since scaled to facilitate over $40 trillion in annual transactions globally.A card-payment system is a multi-party network that connects four core participants: the cardholder, the merchant, the issuing bank (which provides and authorizes the card), and the acquiring bank (which settles funds on the merchant’s behalf). These parties interact through open-loop schemes (Visa, Mastercard) or closed-loop networks (American Express). When a consumer pays, data flow from the merchant’s gateway (which encrypts and routes the information) to a payment processor, then through the card network to the issuer for authorization. Once approved, funds are captured and ultimately settled in batch cycles. Fee structures—interchange paid to issuers, scheme fees to networks, and settlement fees to acquirers—are set by the card networks, vary by region and card type, and are between 2 % and 3 % of the transaction plus a fixed fee (around $0.30). Modern payment facilitators (PayFacs) and orchestration platforms streamline merchant onboarding and optimize routing, boosting acceptance rates while reducing costs.

ACH - The Automated Clearing House (ACH) is a foundational U.S. payments network that moves trillions of dollars annually across over 10,000 financial institutions. Originally developed in the 1970s to replace paper checks, ACH gained national adoption when the federal government began using it for Social Security disbursements. Today, it underpins everything from direct deposit and utility bills to corporate supplier payments. The system handles both credit (“push”) and debit (“pull”) transfers, operating in batches rather than in real time. Each transaction involves an originator, their bank (ODFI), an operator (like the Fed or The Clearing House), and the receiving bank (RDFI). The originating bank assumes liability for the transaction’s legitimacy, especially in debit scenarios—hence the 60-day consumer dispute window. Same Day ACH, introduced in 2015, allows faster processing but still faces limitations, including transaction caps and lack of international reach. Despite its age, ACH remains deeply embedded in U.S. financial infrastructure, favored for its reliability, ubiquity, and low cost ($0.21-$1.50) relative to card networks.

Wire Transfer - Wire transfers are the backbone of high-value, time-sensitive payments in the U.S., facilitated primarily through two systems: Fedwire and CHIPS. Fedwire, operated by the Federal Reserve, uses real-time gross settlement (RTGS) to process each transaction individually and instantly. This is critical for payments such as securities settlements and large corporate deals. CHIPS, run by The Clearing House and owned by major U.S. banks, serves fewer institutions and nets payments between them to reduce liquidity needs, settling most transfers on the same day. Wire transfers are typically irreversible once sent, making them a trusted rail for final settlement. For international wires, banks often rely on SWIFT, a secure global messaging network used by over 11,000 financial institutions, to transmit instructions, though not funds directly. SWIFT-enabled cross-border payments usually settle within one business day but can vary depending on the correspondent bank chain. These systems together move trillions of dollars daily and anchor the global payments infrastructure.

Payments App - P2P payments apps like Venmo and PayPal allow individuals to send and receive money digitally within a closed network where users must create accounts and log in to transact. These platforms typically offer a seamless, low-friction user experience—particularly in developed markets—often enabling free transfers between individuals using linked bank accounts or balances and instant to sub 1 day settlement times. However, cross-border payments are more complex, with added fees, currency conversion, and regulatory friction. While P2P transfers may be free, business-related transactions generally incur a fee of around 3%, making these platforms attractive for casual personal use but relatively costly for merchants or commercial transactions.

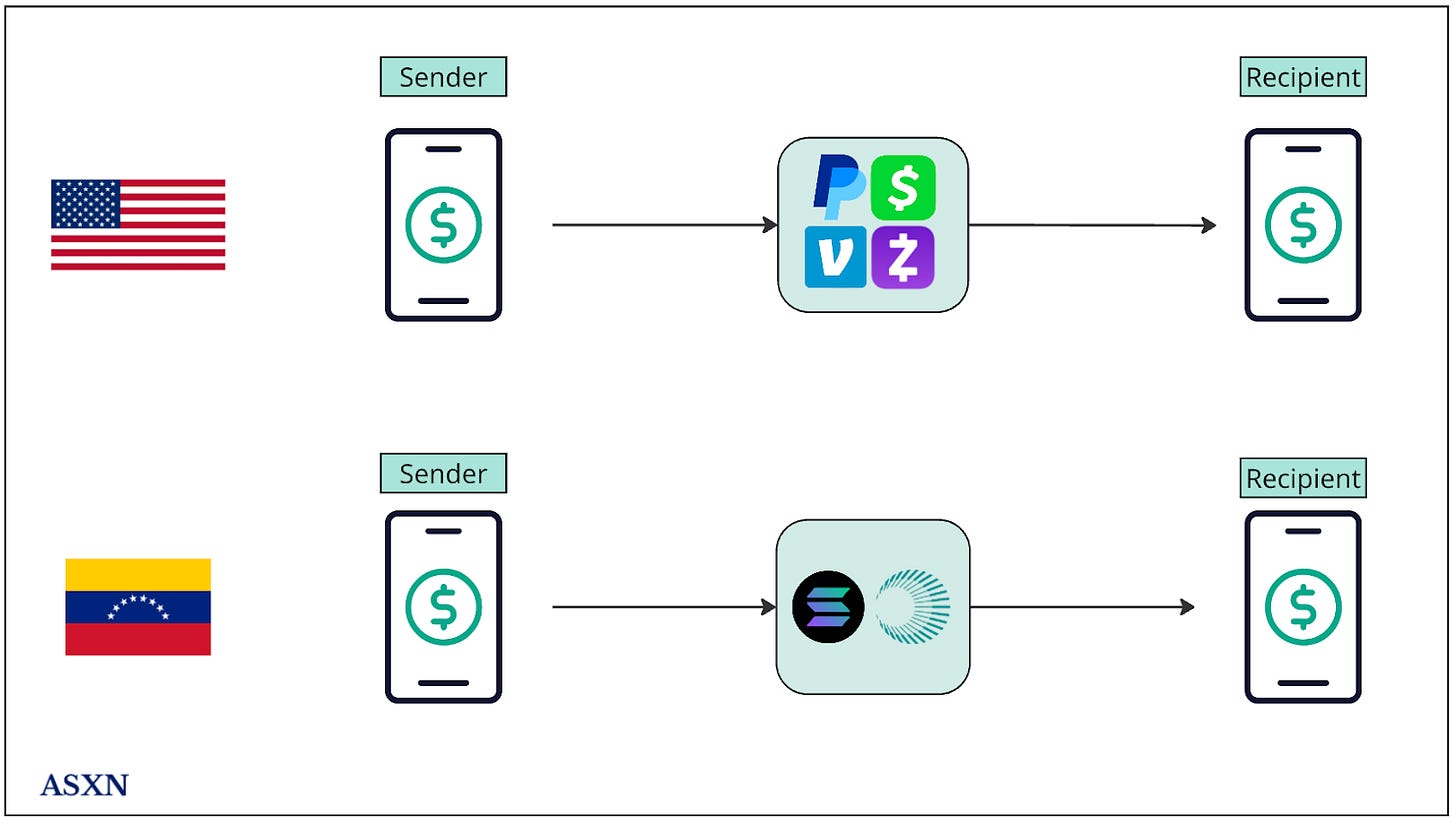

Whilst the banking experience in the U.S is seamless, in countries like Venezuela where inflation is high and trust in the banking system is low, stablecoins represent a way for users to transfer value safely.

A16Z offers a comprehensive overview of these traditional payment methods, detailing their associated fees, settlement times, and operational nuances. Compared to crypto rails, these legacy systems appear outdated—characterized by higher transaction costs, slower settlement, chargeback risks, closed networks, and limited accessibility.

Merchants & Companies

In our view, the most immediate impact from stablecoin-based payments will be felt by U.S.-based companies, particularly those selling into the world’s largest consumer market—the United States itself. This is largely due to the high prevalence of credit card usage and the associated processing fees in the U.S.

A16Z provides a compelling case study highlighting the profit potential of integrating stablecoin payment infrastructure into large-scale U.S. businesses. By reducing payment processing fees to 0.1%, the uplift to profitability can be material:

Walmart reported $648B in FY2024 revenue and likely paid around $10B in credit card fees, against $15.5B in net income. Eliminating these fees could boost its profit by over 60%, significantly increasing its valuation, all else equal.

Chipotle, with $9.8B in revenue and $1.2B in net income, spends approximately $148M on credit card fees. Cutting these fees could lift profits by 12%—a gain unmatched elsewhere in its income statement.